Research Article - (2025) Volume 9, Issue 1

Harvesting Hope: BIMSTEC Nations Paving the Path to Zero Hunger and Sustainable Progress

Shoba Suri*

Department of Nutrition and Physiology, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, India

*Correspondence:

Shoba Suri, Department of Nutrition and Physiology, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore,

India,

Email:

Received: 06-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. IPJFNPH-24-19039;

Editor assigned: 08-Feb-2024, Pre QC No. IPJFNPH-24-19039 (PQ);

Reviewed: 23-Feb-2024, QC No. IPJFNPH-24-19039;

Revised: 13-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. IPJFNPH-24-19039 (R);

Published:

20-Mar-2025, DOI: 10.36648/2577-0586.9.1.36

Abstract

The BIMSTEC comprising of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Nepal is meant to bridge the South Asia and Southeast Asia region. The 2030 SDG goal 2 agenda aims to ‘end hunger, achieve food security and promote sustainable agriculture’. The countries are putting the SDGs into practice by changing the priorities and capacity of the food system to ensure that everyone has access to nutrient-dense food. What's needed may be a transformative action to beat the gaps in achieving the SDG. Some countries like Bangladesh, Bhutan and Thailand have made headway in reducing malnutrition. Investing in women empowerment and agency, water and sanitation and healthy food basket are key to achieving food security. A holistic approach to improve women’s health and nutrition that is scalable and replicable for other countries to learn is required. Investment in agriculture, being the most important economic sector for the BIMSTEC countries could pave way for availability and accessibility of food and address malnutrition. This might also accelerate progress across SDGs on poverty, health, gender, inequality and global climate change.

Keywords

Nutrients; End hunger; Zero hunger; Food security

Introduction

Established in 1997, the Bay of Bengal project for Multi- Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) is a regional cooperation project between South East Asia and South Asia, two important areas. Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Nepal are collectively known as the BIMSTEC countries and classified as low- or middle-income nations. In most BIMSTEC member nations, access to clean drinking water, power, healthcare and education is still a challenge [1]. It is also well known that the general health and nutrition of these countries are poor. Approximately 22% (148.1 million) of children under five years are stunted globally, or over half of all stunted children under five (52 percent or 76.6 million), were found living in Asia in 2022. Of the estimated 736 million severe poor people globally, 29% live in South Asia (216 million of them are extreme poor in South Asia alone). According to FAO estimates in 2021, the number of undernourished people in Asia was more than 425 million, with 58 million added post pandemic, highlighting the region's obvious risk.

Even with consistent economic progress, South Asia continues to fall behind on a number of social, economic and environmental fronts. Furthermore, without South Asia's success, the global SDGs cannot be achieved due to the region's sizable share of the world's impoverished and population [2]. BIMSTEC adopted the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by BIMSTEC that has allowed them to significantly reduce poverty and malnutrition in their states and provide a life where all minimum standards of living are met for their citizens. These goals are especially relevant for South Asia as reiterated in the 2019 joint statement of the first BIMSTEC Ministerial meeting on agricultural cooperation for improved food and nutritional security and poverty alleviation [3].

The paper aims to evaluate the current state of food security, poverty and nutrition outcomes in the BIMSTEC countries. Additionally, it will look at the nutrition policies in each of the BIMSTEC member nations and potential ways to achieve the sustainable development goal on ‘zero hunger’ [4].

Materials and Methods

Unveiling the Challenges and Progress: Poverty Alleviation and Food Security

Arguably, one of the worst issues the world is now facing is global poverty. The poorest people on the planet face basic social problems that include inadequate access to healthcare, gaps in education and food insecurity. Global poverty reduction efforts have practically come to a standstill; by 2030, approximately 600 million people, or 7% of the world's population, would still be living in extreme poverty [5]. Numerous outside forces, such as the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic, Ukraine war and the world's growing population and consequent resource shortages, have contributed to this increase in population. It will be extremely difficult for people living in mostly emerging nations with growing populations to alleviate poverty as a result of these unavoidable developments.

The percentage of individuals who live in extreme poverty worldwide is 12.6% on average, or almost one in eight. 50.7% and 33.4% of the world's extreme poor reside in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, respectively, making them top 2 regions on extreme poor worldwide [6]. The rise in extreme poor in Asian countries shows the phenomena of ‘urbanization of poverty’, that these economies see an increase in urban poverty as they grow more industrialized and globalized [7]. The majority of developing Asia, including Bangladesh, India and other BIMSTEC members, has seen urbanization along with rising rates of slums, poorer living conditions and a decline in food security and increased environmental hazards due to exclusionary policies and climate change.

Sixty percent of the world's slum dwellers live in Asia as of 2018, not to mention the many more that live in substandard circumstances but aren't officially classified as "slums" [8]. While talking about urban poverty, it's also critical to acknowledge that, in contrast to rural poverty, urban poverty has more multifaceted characteristics [9]. These characteristics extend beyond lower incomes and consumption levels to include inequitable access to economic resources, housing and land infrastructure, medical and educational facilities and broader social welfare networks.

The BIMSTEC region is still among the world’s poorest, despite its considerable influence in the last decade. This is evident from the poverty headcount ratio statistics provided by the World Bank, which shows that Nepal had the highest ratio (25.2), followed by India (21.9) and Bangladesh (18.7), Myanmar (17.4), Sri Lanka (14.3), Bhutan 12.4 and Thailand (6.3). Both the GDP per capita and other socioeconomic measures of poverty are still high. With a combined GDP of US$3.6 trillion, the member states of the BIMSTEC have 1.8 billion people living in them. In 2021, BIMSTEC’s intra-regional trade was estimated at US$ 70 billion [10]. Even with the robust domestic economy, social well-being indexes remain low.

In light of the current environmental and socioeconomic conditions, BIMSTEC's sustainable development programs have explicitly attempted to help the starving people and their rising insecurity as resources become scarcer and droughts and floods more frequent. It's also vital to remember that understanding nutrition disparities and their causes is essential to elucidating the causes of disparities in nutrition outcomes and achieving the SDGs and associated global nutrition objectives for all BIMSTEC countries.

Measuring the Impact: A Closer Look at Nutrition Progress

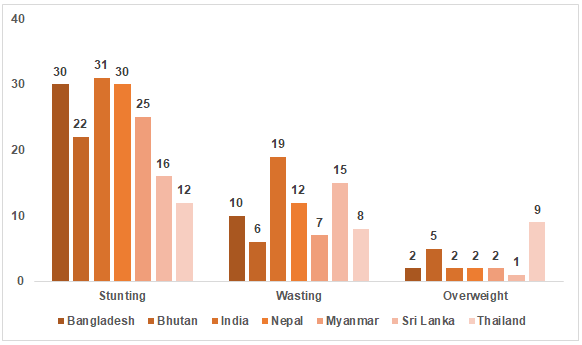

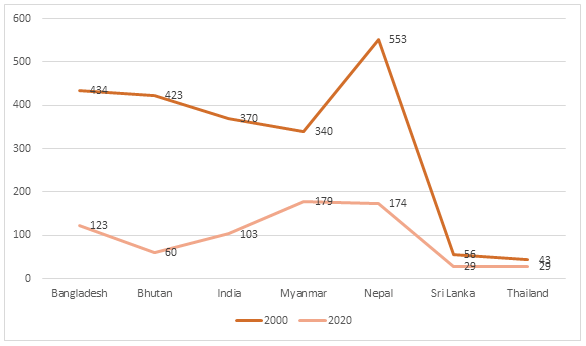

The prevalence rate of malnutrition in under-five children in BIMSTEC countries is shown in Figure 1. The highest percentage of stunting occurs in India (31%), closely followed by Bangladesh and Nepal at 30 percent each and is followed by Myanmar (25%), Bhutan (22%) and Sri Lanka (16%) in that order. In Thailand the rate of stunting is the lowest at 12%. Although stunting has decreased throughout the years in the region, performance varies throughout nations. The only countries that appear to be on track to fulfill the global nutrition targets of a forty percent decrease in the number of stunted children under five are Bangladesh and Thailand; other countries that have made some progress include India, Myanmar, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Figure 1: Stunting, wasting and overweight in underfive children.

On the other side, India has the greatest rate of wasting, which has remained unchanged for decades. The prevalence of wasting in Sri Lanka (15 %) and Nepal (12%) are likewise much higher than the world average of 6.8 percent. Thailand Bhutan and Myanmar have made some headway towards the goal of lowering childhood wasting.

Looking at overweight, Thailand and Bhutan have the highest rates of overweight children in the region, at 9 and 5% respectively. Overweight rates have decreased in Thailand from 10.9 percent in 2012. Rest of the nations are on pace to ensure limiting the rise in overweight children under five years of age, despite the high increase of overweight in South East Asia (7.4%) and South Asia (2.8%) [11].

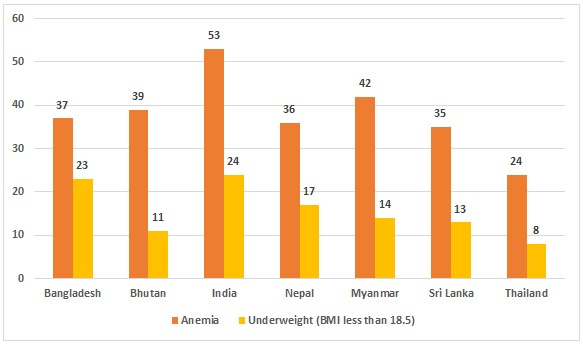

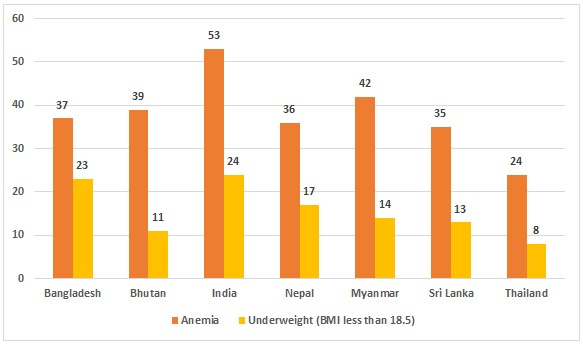

Figure 2, which depicts maternal malnutrition, makes it clearly evident that the majority of BIMSTEC nations have significant rates of anemia in women aged 15 to 49 years. The top three countries on the list are India (53%), Myanmar (42%) and Bhutan (39%). One in three women is anemic in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. This perpetuates a poverty and hunger cycle that spans generations. Pregnancies among adolescents are also linked to a higher chance of stillbirths and neonatal fatalities. Maternal under nutrition and anemia are linked to an increased risk of low birth weight and subsequent stunting or wasting in offspring (Victoria, Christian, Vidaletti, Gatica-Dominguez, Menon and Black). Underweight in women is lowest in Thailand at 8% and highest in India at 24%. Maternity benefits are crucial for women's health and nutrition, as well as for ensuring the success of exclusive breastfeeding. For women working in the public sector, most countries provide paid maternity leave, with certain exclusions for paternity leave or nursing periods. However, for private sector it is dependent on the employer.

Figure 2: Prevalence of malnutrition among women.

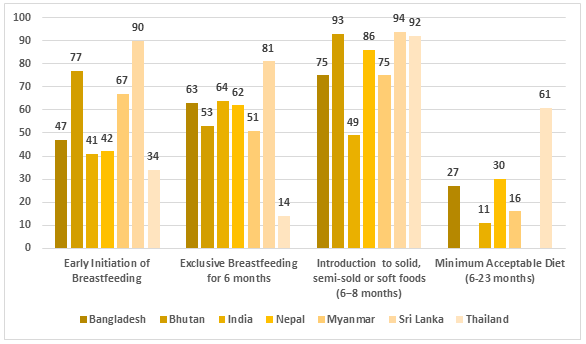

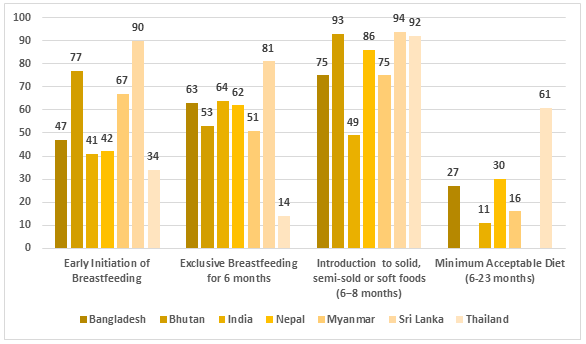

With the exception of Bhutan, Myanmar and Sri Lanka, Figure 3 clearly shows that less than 50% of women start breastfeeding within an hour of birth. The sociocultural practice of providing pre-lacteal meals is linked to the delayed onset of breastfeeding in many South Asian countries. With 81% of women exclusively breastfeeding, Sri Lanka has the highest percentage. The practice of introduction to solid, semi-solid or soft foods (6-8 months) has improved over the years for most of the BIMSTEC countries, except for India with below 50% children being introduced to solid, semi-solid or soft foods, exhibiting a downward trend. Nonetheless, most nations have low rate of minimum acceptable diets (children consuming from 4+ food groups); India (11%), Myanmar (16%), Bangladesh and Nepal at 27 and 30% respectively and highest at 61% in Thailand. No recent data is available for Bhutan and Sri Lanka. Impaired growth and development can result from suboptimal feeding practices, which can raise the risk of illness. To enhance feeding practices, more behavioral modification and education on feeding practices are required.

Figure 3: Infant and young child feeding practices in children.

Tracking Health Outcomes: Achievements so Far Known as the "Asian Enigma" of under nutrition, the majorities of BIMSTEC nations has poor health outcomes and have made little improvement in recent decades. However in past 2 decades, the under-five mortality rate has drastically decreased in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar and Nepal as shown in Table 1 below.

| Country |

2001 |

2021 |

| Bangladesh |

81 |

27 |

| Bhutan |

73 |

27 |

| India |

88 |

31 |

| Myanmar |

87 |

42 |

| Nepal |

75 |

27 |

| Sri Lanka |

16 |

7 |

| Thailand |

21 |

8 |

Table 1: Under-five mortality rate (per 1000 live births).

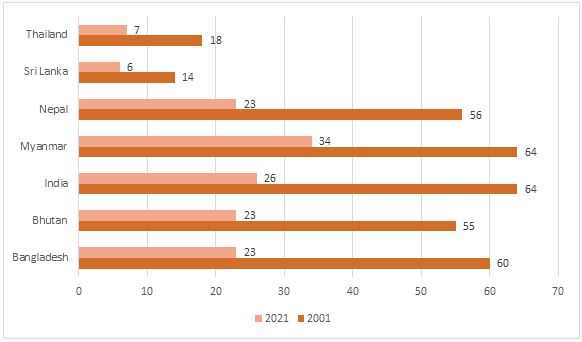

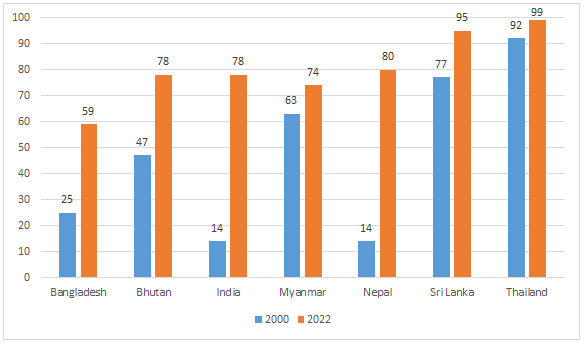

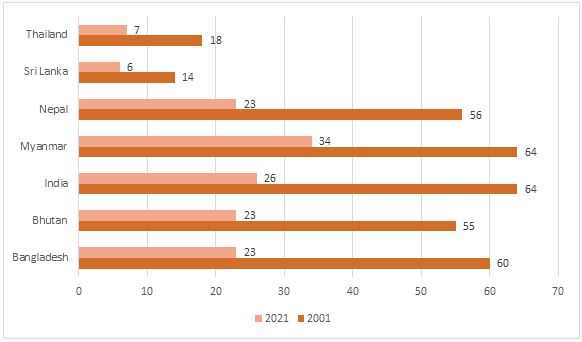

As evident from Figure 4, BIMSTEC member nations have greatly reduced their infant mortality rates, demonstrating a great accomplishment in terms of health improvement. Sri Lanka had the lowest infant mortality rate in 2021, while Myanmar had the highest at 34%. The highest decline in prevalence point has been seen India (38%) and Bangladesh (37%).

Figure 4: Infant mortality rates (per 1000 live births).

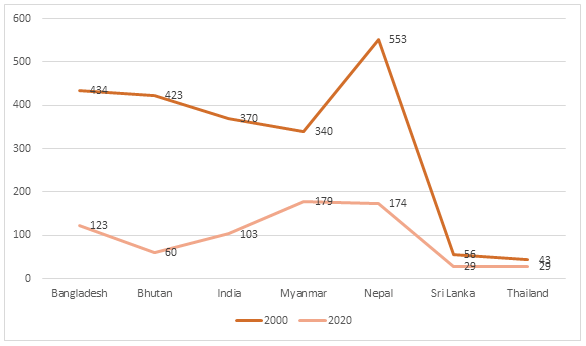

The incidence of maternal mortality has been steadily declining in each of the seven BIMSTEC nations (Figure 5). The largest decrease in maternal mortality occurred in Nepal, where it went from 553 in 2000 to 179/100,000 live births in 2020. Through a variety of community-based and national policies, Nepal has significantly improved the delivery of healthcare in order to prevent maternal and infant mortality. It should be mentioned that, in 2000, the rates of maternal mortality in Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Myanmar were much higher than those in Sri Lanka and Thailand, with respective rates of 56 and 43 per 100,000 live births. Both Sri Lanka and Thailand have prioritized universal health coverage and have strengthened basic healthcare. The steady decline in maternal death rates reflects the degree of advancement in healthcare and delivery over the past 2 decades.

Figure 5: Prevalence of maternal mortality (per 100,000 live births).

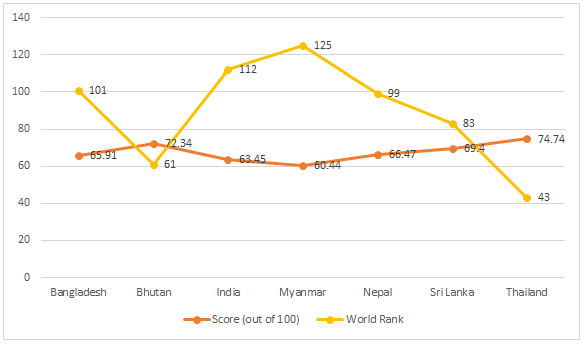

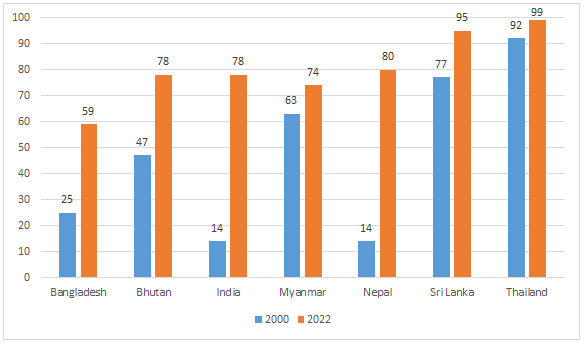

A few of BIMSTEC nations like India and Nepal have made tremendous progress than others in terms of better sanitation (Figure 6). The proportion of persons utilizing at least basic sanitation facilities has grown by 64 and 66 percentage point in India and Nepal respectively. The percentage of population in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar who receive basic sanitation services has likewise steadily increased; and Thailand reaching a near 100% in providing basic sanitation services. Evidence indicates significant impact of both public and private health expenditure on health status in BIMSTEC region for reason of improved healthcare facilities [12].

Figure 6: Percentage population availing at least basic sanitation services

Looking at Table 2 it is clear that the health expenditure as percentage of GDP has gone up drastically for Myanmar (2 in 2000 to 4.62% in 2020) and Thailand (3.1 in 2000 to 4.36% in 2020). However, on the other hand, with the exception of Thailand and Bhutan, all BIMSTEC nations have out-of-pocket expenditure around 50% and above [13].

| Country |

Health expenditure (% of GDP) 2000 |

Health expenditure (% of GDP) 2020 |

Out of pocket expenditure (% of health expenditure) 2020 |

| Bangladesh |

2.11 |

2.63 |

74 |

| Bhutan |

4.45 |

4.37 |

15.42 |

| India |

4.03 |

2.96 |

50.59 |

| Myanmar |

2 |

4.62 |

78.2 |

| Nepal |

3.13 |

5.17 |

54.17 |

| Sri Lanka |

4.25 |

4.07 |

46.58 |

| Thailand |

3.1 |

4.36 |

10.54 |

Table 2: Health sector budget in the BIMSTEC region (Year)" health expenditure (% of GDP) in BIMSTEC region.

Results and Discussion

Tracking Progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Achieving the UN's 2030 agenda for sustainable development demonstrates the revolutionary global commitment to eradicating hunger and poverty. Theoretically, creating an inclusive and sustainable society is far easier than it is in practice due to national, international and economic constraints. The 17 sustainable development goals and the 169 goals that go along with them are especially important for South Asia, which is home to about 60% of the world's undernourished children and about 36% of the world's impoverished people [14].

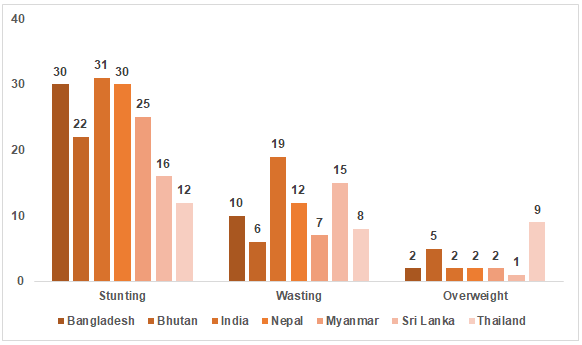

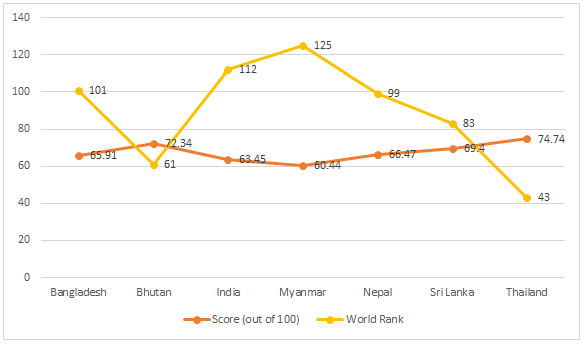

Reducing inequality and establishing sustainable patterns of consumption and production are two of the major social tendencies that the sustainable development goals seek to reverse. Though South Asia and especially India, has underperformed in attaining the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), reaching the sustainable development goals by 2030 will be an optimistic endeavor. The overall performance of BIMSTEC countries towards achieving SDGs is depicted in Figure 7. The performance scores out of 100 shows the progress; all countries are around 70% of SDG achievement. On the ranking, Myanmar is far behind followed by India and Bangladesh [15].

Figure 7: The overall performance of BIMSTEC countries towards achieving all 17 SDGs.

In addition to the challenges that many nations have in their efforts to meet the SDGs by 2030, COVID-19 has made failure to do so much more likely. By the end of 2019, the fifteen-year global effort by people to accomplish the seventeen sustainable development goals has already gotten off course, according to the sustainable development goals report 2020. Figure 7 displays the world ranking and the BIMSTEC nations' performance on the SDGs (out of 10). Thailand had the highest performance among the BIMSTEC nations, scoring 74.7, while Myanmar has the lowest, scoring 60.4. Five of the seven countries are located in South Asia and the most recent data available indicates that this region has shown modest progress to meet the 2030 SDG 2 ‘zero Hunger’ goal [16].

Since 2015, least progress has been achieved towards SDG 2, Zero Hunger. and several nations throughout the world appear to be reversing their previous gains in light of the Covid-19 outbreak. The growth in both overweight and undernourished individuals is a contributing factor to the poor development. In most of the BIMSTEC nations, achieving or making progress towards SDG 2 has been difficult, with India accounting for a sizable portion of the undernourished. India's goal of eliminating undernourishment would bring the world one step closer to reaching its zero hunger goals. With 96,778 per million confirmed cases and 874 per million deaths, the COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as the greatest humanitarian and economic disaster of the twenty-first century, across national borders. Given the increasing hurdles faced by COVID-19, there is now less chance than ever of successfully fulfilling the UN sustainable development goals by 2030 [17].

Government Initiatives in BIMSTEC Region

States from all around the world have started implementing national policies, programmes and community-led projects in an effort to meet the UN 2030 sustainable development goals. Eliminating world poverty and all of its aftereffects is the biggest global problem. The governments that make up the BIMSTEC have enacted policies aimed at guiding their countries towards the 2030 SDG objectives.

The Bay of Bengal Initiative's polycentric strategy encompasses private and public partners, with stakes in politics, society, the environment and the economy [18]. This collaborative framework contains directives and policies that aim to promote sustainable development. The mission and objectives of BIMSTEC are wide-ranging, including the scientific, technological, social and economic domains. Since environmental issues worsen social, political and economic conflicts in the area, they are crucial in combating poverty. Examples of these issues include climate change and environmental degradation. Enhancing food and agriculture may significantly contribute to achieving the other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by boosting economic growth and addressing climate change [19]. Building resilience against natural catastrophes is necessary to combat global hunger, which is a major aspect of the world's problems with food insecurity.

Fisheries, power plants and wastewater treatment plant management are a few of the projects undertaken by the Bay of Bengal association for sustainable development [20]. This serves as a forum for small business owners and innovators from member states in addition to these public projects. Their shared business models address challenges including lowenergy wastewater solutions, power projects and sustainable aquaculture along the coast and fisheries monitoring and surveillance. Given that the Bay of Bengal is an epicenter of the "World's hazard belt," it is crucial to pay attention to both the surroundings and the bay itself. The Bay of Bengal has a triangular form, flat coastline topography and shallow depth.

Ever since the United Nations ratified the 2030 sustainable development goals, it is the duty of every state to implement policies that advance these objectives. Nepal, implemented the multi-sector nutrition plan-II in 2018 with an aim to decrease low birth weight, enhance the nutritional status of children under five and alleviate energy insufficiency in women. This plan aims to improve maternal, adolescent and child nutrition through the scaling up of essential nutrition interventions. In doing so, Nepal increased the scope of its multisector nutrition programmers, created national campaigns to promote healthy eating habits and promoted collaboration in exchanging best practices for nutrition improvement. Data show that the nation's nutritional conditions have improved, with the frequency of wasting and stunting among children under five years old declining also low birth weight.

Bhutan's government uses five-year plans to address development in the country. The current plan, which is the eleventh five-year plan, seeks to accomplish sixteen "national key result areas" that are grounded on regional and global commitments, e.g. the 2030 sustainable development goals of the United Nations. The food and nutrition security policy of Bhutan, which was implemented in 2014, recognizes the necessity of a multi-sectoral strategy to guarantee nutrition security. The Bhutanese government prioritized nutrition and created a national school and nutrition programmer to alleviate shortages in certain micronutrients.

Bangladesh passed a National Nutrition Policy in 2015 with the aim of achieving the sustainable development goals of the United Nations by 2020. Stunting is the most prevalent kind of under nutrition in the nation, indicating a serious chronic undernourishment issue. To address the malnutrition issues in the nation, the Bangladeshi government has included nutrition as a core component of family planning and public health services. The National Nutrition Policy's overarching objective is to raise Bangladeshis' nutritional status. The strategy placed a strong emphasis on the need to guarantee sufficient nourishment for all age groups, including men, women, children and expectant mothers. Through the promotion of investments in nutrition-sensitive agriculture and the improvement of domestic food security, as guided by policy.

Sri Lanka is suffering through a triple burden of malnutrition over nutrition, under nutrition and micronutrient deficiencies as a nation going through an economic transformation. The introduction of a universal food subsidy programme in 1942 marked the beginning of the Sri Lankan government's interventions to combat food insecurity. Sri Lanka has made progress in addressing food insecurity since the UN's 2030 sustainable development goals were formed. The Thriposha programme was first implemented in 1970. Over the past five years, as household income has increased, the ratio of food expenditures in total household income expenditures in Sri Lanka has been gradually falling. Since 2015, Sri Lanka's nutritional results have significantly improved due to the country's comprehensive health infrastructure, as measured by social welfare metrics. Sri Lanka’s country strategic plan for 2023–2027 aims to reduce vulnerability through an integrated resilience and nutrition-sensitive approach that layers and sequences programming, as well as to restore and improve food security and nutrition by building in-country capacity.

Thailand has combined a national food safety and nutrition strategy with a framework for food security since ratifying the UN's 2030 sustainable development goals. Thailand had seen economic progress and a decline in undernourishment even before the UN SDGs were established. Between 1990 and 2012, undernourishment decreased by 87% while GDP climbed by 113%. The government's policy-driven initiatives have resulted in a downward trend in nutritional outcomes, including stunting and underweight, in Thailand. In spite of the progress made in reducing hunger, overweight is a new nutritional problem. Overweight problems affect one-third of both adults and children (Sakboonyarat, Pornpongsawad, Sangkool, Phanmanas, Kesonphaet, Tangthongtawi, Limsakul, Assavapisitkul, Thangthai, Janenoppakarnjana, varodomvitaya, Dachoviboon, Laohasara, Kruthakool, Limprasert, Mungthin, Hatthachote and Rangsin 2020).

For India to meet the sustainable development goals of the UN by 2030, the National Nutrition Policy is a crucial step forward (NNP). India's high rates of maternal and child under nutrition have persisted in spite of the government's policies, plans and programmes. The goal of the National Nutrition Policy, which was first implemented in 1993, is to guarantee that every child, adolescent girl and woman has the best possible nutritional status. Along with the gains in India's general nutritional status brought about by this national plan, the Poshan Abhiyan also known as the National Nutrition Mission, has also been a positive step in the right direction (NNM). The goal of the policy is to establish a communications and information monitoring system that would allow for the surveillance of nutritional status throughout the nation. Though India is already lagging behind in reaching the 2030 SDGs due to the COVID-19 epidemic, the policy's implementation presents challenge.

While Myanmar is on track to fulfill global target for exclusive breastfeeding and overweight children under five, it is still behind schedule for other nutritional indicators on anemia in women and stunting and wasting in fewer than five children. Myanmar passed the National Plan of Action for Food and Nutrition, or NPAFN, to ensure that its citizens have proper access to wholesome, well-balanced food for their physical and mental development. The NPAFN policy has assisted Myanmar in making significant progress towards achieving the 2030 sustainable development objectives by boosting and diversifying domestic food production, encouraging wholesome diets and reducing food-borne infectious illnesses. The political and social issues that Myanmar being one of the least developed countries in the world is facing are multifaceted. Food insecurity is a direct result of these and significantly impedes the nation's efforts to reduce hunger (SDG 2).

Building Resilience: Uniting Efforts for Food Security

Millions of people were already at risk of food price shocks and other catastrophes due to conflict, climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. The conflict in Ukraine is now transforming a crisis into a disaster due to its impact on global fuel, fertilizer and food prices as well as supply. The global hunger index score for 2022 reveals that the fight against hunger has come to a standstill. Additionally, indicators on child stunting and obesity rates are rising further highlighting the catastrophic situation.

According to the state of food security and nutrition in the World 2022, there were up to 828 million undernourished individuals worldwide in 2021, which is a sign of chronic hunger. Furthermore, the Global report on food crises 2022 states that approximately 193 million people experienced severe hunger in 2021, an increase from 2020. These effects are currently being felt throughout South Asia, Central and South America, Africa's sub-Saharan region and beyond. With the third global food price crisis in the last fifteen years, it is more evident than ever that the existing state of our food systems is not sufficient to eradicate hunger and poverty in a sustainable manner.

The BIMSTEC platform gives the countries of South and Southeast Asia a degree of regional connection that improves economic cooperation because of the present collaboration of BIMSTEC members via common ambitions of growth, development, trade and technology. Economic downturns and slowdowns increase unemployment, lower earnings and make it more difficult for the impoverished to obtain food and other basic social services. A further factor in the afflicted population's worse nutrition is the rising cost of access to wholesome, high-quality meals. Global growth is at its lowest point since the global financial crisis ten years ago, which unfortunately suggests that there may soon be another global economic depression.

Policies and resilience capacities must be developed to counteract the subsequent fall in buying power that results from these economic downturns in order to safeguard the food status of individuals suffering economic shocks. Trade policy may increase the availability of nutritious foods and generate demand for them, which can have a significant impact on nutritional results in food insecure areas. But trade policy frequently exacerbates types of malnutrition because it almost never takes nutritional outcomes or healthy diets into consideration. For instance, there are a variety of elements that influence the health effects of trade changes pertaining to food and agriculture and cross border investment acts as a catalyst for the increased intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, which has led to an increase in overweight and obesity worldwide.

Multi-sectoral approaches for decreasing poverty are necessary to address the social inequities that are sustained by the trajectory of economies worldwide. Food accessibility in the physical sense is crucial; in particular, by encouraging the productivity of underprivileged farmers, food production and availability for the underprivileged nationwide improved. Facilitating the trading of food items also makes food commodities more accessible to underprivileged customers at reduced costs. Food availability on a physical level is vital, but so is economic accessibility to food. Long-term investments in social protection systems, employment promotion initiatives, assistance for impoverished farmers and rural development initiatives are necessary to guarantee that the poorest segments of society have access to nutrient-dense food. Like fundamental investments in health, education and income can help prevent the causes that are contributing to malnutrition from getting worse.

In addition to its negative effects on global food security and the fragility of the global economy, climate change is a major obstacle to reaching the 2030 sustainable development goals. Climate change impacts the availability, accessibility, utilization and food system stability. The first people impacted by climate change will probably be those who are already food insecure. Policies that safeguard food security by adjusting to climate change must be implemented in order to reverse this tendency. In addition to the necessary changes at the governmental level to accomplish the 2030 sustainable development goals, community-led efforts can be extremely important in reducing global food insecurity.

Nutrition and Home gardens have great potential to improve the nutritional landscape of a society from the ground up. Individuals are empowered to cultivate their own nutrientrich produce by using these small-scale plots as centers for growing a wide variety of fruits, vegetables and herbs. Communities may increase their access to fresh, locally sourced food and diversify their nutritional options by encouraging home gardens. With a balanced diet full of essential vitamins, minerals and micronutrients, the variety of crops greatly enhances nutritional intake. Additionally, home gardens promote self-sufficiency by lowering reliance on outside food sources. They are essential to improving food security, particularly in areas that are economically constrained or vulnerable to interruptions in the food supply chain. This strategy helps to create a more resilient community against food shortages and sustainable model for food security.

The social, political and economic context of today's developing nations, as well as the resources available for intervention, constrain the practical strategies that may be used to alleviate food insecurity there and elsewhere. Home gardens and community-based nutrition gardens have been shown to be significant additional sources that give communities livelihood and nutritional security on a global scale. There are many different types of home gardening, including mixed, kitchen, backyard, farmyard, compound and homestead gardens. It is a long-standing and popular activity. People are frequently forced to reduce their consumption and settle for low-nutritional food due to food insecurity and financial difficulties. Due to the absence of essential vitamins, minerals and other micronutrients, this has a negative impact on one's health; in fact, almost 35% of deaths globally are linked to nutritional deficiencies. By promoting the yearround production and availability of nutrient-dense foods, athome fruit and vegetable farming helps to enhance diet quality and treat micronutrient shortages.

In addition to increasing food availability, diversity and general health, home and community gardens can raise the socioeconomic standing of low-income households. Research indicates that home gardens support entrepreneurship and rural development in addition to generating revenue, enhancing livelihoods and improving household economic wellbeing. According to Mitchell and Hanstad, review of case studies, home gardens have a variety of positive effects on a household's financial health. Growing gardens may become a small business and the money made from selling items grown at home can provide disposable income for other household needs.

It has been shown that nutrition gardens are crucial for enhancing both dietary variety and national food security in order to increase nutritional status. Numerous case studies conducted in the BIMSTEC nations have demonstrated their viability as a paradigm for improving food security and diversity. In order to address malnutrition, community and nutrition gardens can be a significant factor in improving national food security and dietary diversity. Families with kitchen gardens had higher diversity and amount of fruits and vegetables, according to a research done in Bangladesh. In rural Bangladesh, another form of kitchen garden has shown to reduce vegetable costs, increase fruit and vegetable intake and generate income. Research has shown that school gardens in Nepal and Bhutan can positively impact children's food preferences and lead to changes in their health and nutrition habits. A Sri Lankan study proposes the home garden as a viable strategy to raise household nutritional status and increase food security. States in India like Odisha and Gujarat have made use of backyard areas to cultivate seasonal fruits and vegetables, improving the family's financial situation and supplying wholesome food.

An illustration of how community-led nutrition gardens might aid in closing the nutrition gap in rural families can be found in India's reliance nutrition garden. According to a research on the reliance nutrition garden, homes that had one of these gardens consumed more nutritious food. According to the study, these nutrition gardens resulted in lower food expenses and 62 percent of rural houses meeting their vegetable requirements. Therefore, the nutrition gardens may offer a low-cost, micro solution for ensuring wholesome food and a balanced diet.

Conclusion

As per above evidence, the BIMSTEC countries are not on course to achieve zero hunger by 2030. It is clear that several BIMSTEC countries were lagging below the zero hunger goal even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. As an impact, by 2030, there will be more than 840 million hungry people worldwide.

The elimination of hunger and malnutrition is a necessary condition for the attainment of the sustainable development goals. To attain the objective of zero hunger, a robust and sustainable food system is required. Comprehensive measures to guarantee that food is accessible to everyone can help achieve this. Given the situation, there is a need for fresh approaches and concentration on developing capacities at the individual and community level.

In order to promote food systems that provide better nutrition and resilient, sustainable communities, nations may benefit from each other's accomplishments and scalable model development. "Sustainable food systems ensure that everyone has access to food security and nutrition while maintaining the economic, social and environmental foundations necessary to ensure food security and nutrition for future generations."

Long-term efforts for the elimination of all types of malnutrition will need investing in nutrition coupled with a multi-sectoral strategy that involves both nutrition-specific programmes that also enable women's empowerment along with and nutrition-sensitive measures. "Achieving zero hunger is a shared commitment," which calls on nations to be persistent in their efforts to achieving it.

References

- Mathur OP (2013) Urban poverty in Asia. Asian Development Bank, Metro Manila, Philippines. 1-22.

[Google Scholar]

- BIMSTEC (2019) Joint statement of the first BIMSTEC ministerial meeting on agriculture. Myanmar.

- BIMSTEC (2022) 5th BIMSTEC summit.

- Holmgren S (1994) An environmental assessment of the Bay of Bengal region. Bay of Bengal Programme (BOBP).

[Google Scholar]

- Brownrigg L (1985) Home gardening in international development: What the literature shows (including an annotated bibliography and inventories of international organizations involved in home gardening and their projects).

[Google Scholar]

- Calvet-Mir L, Gomez-Baggethun E, Reyes-Garcia V (2012) Beyond food production: Ecosystem services provided by home gardens. A case study in Vall Fosca, Catalan Pyrenees, Northeastern Spain. Ecol Econ. 74:153-160.

[Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi I (2019) The Bay of Bengal association for sustainable development: A speculative framework for governance.

[Google Scholar]

- ESCAP U (2018) South Asia's march towards achieving the sustainable development goals.

- FAO (2015) Bangladesh National nutrition policy 2015: Nutrition is the foundation for development.

- World Health Organization (2019) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2019: Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Food and Agriculture Org.

[Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020: Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Food and Agriculture Org.

[Google Scholar]

- UNicef (2023) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023: Urbanization, agrifood systems, transformation and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2022) The state of food security and nutrition in the World 2022: Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. Food and Agriculture Org.

- FAO (2001) Food security and trade–an overview.

- Al W, Orking G, Clima O (2008) Climate change and food security: A framework document. FAO Rome.

[Google Scholar]

- FAO (2014) Food and nutrition security country profiles-Thailand.

- FAO (2018) Sustainable food system-concept and framework.

- Ferdous Z, Datta A, Anal AK, Anwar M, Khan AM (2016) Development of home garden model for year round production and consumption for improving resource-poor household food security in Bangladesh. NJAS Wageningen J Life Sci. 78:103-10.

[Google Scholar]

- Development Initiatives (2022) Global nutrition report 2022: Stronger commitments for greater action.

- Islam TT, Newhouse D, Yanez-Pagans M (2021) International comparisons of poverty in South Asia. Asian Dev Rev. 38(1):142-175.

[Google Scholar]

Citation: Suri S (2025) Harvesting Hope: BIMSTEC Nations Paving the Path to Zero Hunger and Sustainable Progress. J Food Nutr

Popul Health. 9.36.

Copyright: © 2025 Suri S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution

License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source

are credited.