Research Article - (2025) Volume 11, Issue 1

Empowering Healthcare through Education: Is the Primary Trauma Care Course Impactful in Sub-Saharan Africa?: A Literature Review

Cherinet Osebo1,2*,

Jeremy Grushka1,

Dan Deckelbaum1 and

Tarek Razek1

1Department of Surgery, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

2Department of Emergency Surgery and Obstetrics, Hargelle Hospital, Hargelle, Ethiopia

*Correspondence:

Cherinet Osebo, Department of Surgery, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec,

Canada,

Tel: 5146219028,

Email:

Received: 22-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. IPJICC-24-18949;

Editor assigned: 24-Jan-2024, Pre QC No. IPJICC-24-18949 (PQ);

Reviewed: 08-Feb-2024, QC No. IPJICC-24-18949;

Revised: 13-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. IPJICC-24-18949 (R);

Published:

20-Jan-2025, DOI: 10.36648/2471-8505.11.1.56

Abstract

Background: Injury-related mortality and morbidity contribute significantly to public health concerns. Insufficient resources, infrastructure and workforces, infancy trauma care system, and training programs in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) extended the injury burden, resulting in increased deaths. In such cases, the proposed solution is to provide a resource-friendly, highly impactful training approach. The Primary Trauma Care (PTC) course was developed to provide a reasonable replacement for local resources, given that Advanced Trauma Life Support training (ATLS) is unaffordable in resource-limited regions. This study focused on evaluating the PTC training impacts on SSA clinicians.

Materials and Methods: We reviewed the literature by searching MEDLINE (Ovid interface), Embase (Ovid interface), and African journals online databases to identify relevant peer-reviewed articles. Studies were included if the topic focused on PTC training in SSA and addressed the impacts of training on injury management assessed participants and patients’ outcome measures, and trainees were hospital-based healthcare practitioners.

Results: All training was held entirely in SSA’s settings. The bulk of studies reported on nurses and clinical officers (58.9%), followed by physicians (35.5%) and medical students (5.6%). Three studies were identified as Kirkpatrick level 2 evidence, and one reflected level 4. All four studies found that taking a PTC course improved knowledge of injury management (p<0.05). Except for a single study that represented a reduction in trainees' confidence (p<0.03), the rest three demonstrated improvements in confidence and skill attainment (p<0.05). One study discovered lowering traumatic mortality rates after a PTC course (p<0.01).

Conclusion: Following the PTC training, clinicians experienced significant advancements in knowledge in managing critical trauma patients and noted departmental infrastructure enhancements. We fully appraise the PTC training program as a first-class course for SSA with follow-up refresher sessions to ensure sustainability and improve trauma care. Further, a comprehensive institutions-based study is recommended to understand the training’s impact on patient outcomes.

Keywords

Trauma training; Sub-Saharan Africa; Primary trauma care; Trauma care improvements

Introduction

Trauma and injury are more deadly and morbid than tuberculosis, HIV, and malaria combined [1]. The injury burden disproportionately affects SSA, accounting for over 90% of injury-related death [2]. Several factors contribute to the disparity of injury-related morbidities and mortalities globally, including a paucity of infrastructure, trauma centers, and resources and inadequate training of healthcare personnel [3,4]. Among the significant causes of death in SSA are traumas from conflict, interpersonal violence, and traffic fatalities. The substantial burden of morbidity experienced by those who survive their injuries results in an economic cost of 6% of years lived with disability globally [5].

Various strategies have been suggested to enhance trauma care in SSA, including but not limited to developing a prehospital trauma care system, optimizing trauma facilities, enhancing trauma care, and advancing trauma training [6]. Despite distinct training types of existences, they consistently have favorable influences on clinical effectiveness, such as injury-linked morbidities and mortalities alongside costefficiency [7]. Providing front-line medical personnel with a structured approach to promptly evaluating and treating trauma patients is critical. Although such training in High- Income Countries (HICs) requires emergency medicine and surgical personnel, trauma education courses for SSA professionals remain restricted.

The ATLS program, created by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) in 1978, is an acknowledged norm for the initial evaluation and treatment of critically injured patients [8]. Widespread introductions of ATLS in trauma care have boosted employee knowledge and clinical competence. In affluent nations, trauma-related fatality rates have significantly decreased during the past years. Such improvements in trauma management and road safety are related to the construction of trauma networking and extensive retraining of the trauma workforce through deploying courses, including ATLS [9,10]. While a universal standard is desirable, considerable obstacles to implementing ATLS in SSA exist, including challenges in contextualization for low-income experts, inadequate infrastructures, and prohibitive costs for the hosting country [11]. Studies on COSECSA (College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa) nations revealed insufficient infrastructure in addressing trauma provision, including a lack of designated trauma units and trained personnel resulting in the injured being confronted with delays in accessing essential trauma care [12].

According to Mongolian research, the minimum annual cost of the ATLS course is $10,709, alongside the $84,875 expense to train local instructors initially [13]. The ACS mandated that surgeons be ATLS site directors [14]. While committed surgeons are critical for program success to improve trauma care, other non-surgical front-line clinicians frequently drive similar initiatives. For instance, emergency medicine emerged as a robust specialty in some low-income regions, resulting in taking the lead initiatives to manage critical trauma patients. Furthermore, ATLS also restricts participants to physicians and advanced practitioners. However, task shifting is widespread in a context with limited resources, and several front-line acute caregivers are not physicians in several SSAs [15].

Programs such as Primary Trauma Care (PTC) courses were introduced to tackle the challenges above [16]. According to the PTC website, trained workforces exceeded in over 80 nations [17]. Although PTC educates diverse teams on traumatology topics, whereas ATLS focuses on surgical personnel, these courses are built up with the fundamental principles of primary and secondary surveys like ATLS, resulting in affordable and long-lasting. Although such classes responded to core criticism from ATLS accessibility, effectiveness in reducing injury-linked mortality remains and requires further studies [18,19]. A five-day "cascading model, 2-1-2" is required for the PTC training for success [17]. The initial two-day training identifies potential instructors; these individuals are urged to attend the subsequent one-day instructor session on the third day. After receiving training, the newly minted instructors should run a two-day “provider” training under a direct external supervisor, finishing five days of instruction [20].

The benefit of PTC remains multidimensional, including receiving cost-free initial training for emerging regions with an official request. Further free online resources are available for the course, including instructors’ guidelines and training resources [19]. Attendees in the PTC foundations are welleducated through lectures, group discussions, and practice sessions. The PTC topics discussed comprise initial evaluation utilizing primary and secondary surveys, basic and advanced airway, and other skill sets in managing head, chest, abdomen, pelvis, spine, and limb trauma. Instructors are encouraged to tailor the curriculum considering trainees’ skills and locally available resources, whereas the course manuals and tools are readily accessible to assist them.

To date, trauma education's overall scope and efficacy are unrecognized in SSA. Notably, it lacks strong consensus on the course's comprehensiveness, practicalities, and costeffectiveness that entirely focuses on SSA rather than presenting collectively as Low-and-Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). We felt it was inappropriate to generalize the PTC course availability, suitability, and operations in all LMICs with the same scale. For instance, comparing the PTC training outcomes and affordability in China (an upper middle-income country) with Burundi (a low-income country) may differ for various reasons, including resource allocations. Still, both are categorized as LMICs by the United Nations human development index. Therefore, we are motivated to evaluate the published experience entirely in SSA, aiming to provide conclusive insight into PTC training effectiveness, availability, and operations. We further determine PTC program capabilities on replacing ATLS in SSA through measuring advancement in patients’ outcomes and practitioners' improvements in skills, knowledge, and confidence when managing the critically injured one alongside course affordability and multi-disciplinarity.

Materials and Methods

This review followed the PRISMA–ScR guidelines: PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. We opted to conduct a literature review using structured research questionnaires.

Search Strategy

We conducted a literature review of published articles in SSA related to the PTC course. We enlisted the assistance of a research librarian at the McGill University Health Centre to aid our search of the MEDLINE (Ovid interface), Embase (Ovid interface), African journals online databases, and global health (Ovid interface) databases. The search strategy included the following words "primary trauma care*" or "trauma course*" or “injury care education*" or "PTC training*" and “Sub- Saharan Africa*” or “Africa*” to identify relevant peerreviewed articles in PTC training. The search was limited to articles published between January 1st, 2000, to December 31st, 2022 in the English language. Additionally, the reference lists of these publications were searched for additional relevant articles related to trauma training.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if the topic focused on PTC training in SSA and addressed the impacts of training on injury management; participants were facility-based health practitioners, including but not limited to doctors, nursing staff, clinical officers, residents, and medical students. Additional inclusion criteria focused on outcome measures; participant-related variables like knowledge, skills, and confidence; and patient-related metrics like mortality, morbidity, and complications. Studies were excluded if the courses were held in other than SSA; the training was not the official PTC course or was adapted from the PTC course; ATLS; pre-hospital care providers and community health workers; no details on the structure of the education were provided; and the courses only used subjective measurement tools with no skill evaluation components and non-English papers.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

CO and TR screened the titles and abstracts of the identified publications for relevance. Articles that passed the two screening stages were then charted for relevant data. Titles and abstracts were reviewed, publications meeting the inclusion criteria were collected, and the papers were reviewed. Exclusion criteria were applied to all abstracts and the full articles. Publications that satisfied inclusion criteria were selected based on training locations; descriptions; certified healthcare providers; relevant outcome measures, and finances. Table 1 presents the adapted Kirkpatrick fourlevel training evaluation model, a commonly used framework for measuring training outcomes' effectiveness (Table 2).

| Kirkpatrick level |

Description |

Training outcome measures |

| Level 1-Reaction |

Participants’ feelings towards training values and relevance in their daily duties. |

Subjective evaluations. |

| Level 2-Learning |

Participants acquired the training's expected knowledge, skills, confidence, and commitment. |

Objective pre/post-tests Confidence measurements. |

| Level 3-Behavior |

Participants apply daily job objectives and skills learned during training. |

Objective skill measurement utilizing simulation cases, OSCE, or assessing actual injured patients. |

| Level 4-Results |

Training influenced participants’ performance/outcomes. |

Trauma care improvements include mortality, morbidity or complications, or overall trauma system enhancements. |

Table 1: Kirkpatrick model for evaluating training.

| First Author |

Location |

Course |

Attendees |

Course assessments modes |

Outcome |

Kirkpatrick evaluation levels |

| Peter, 2015 |

COSECA countries |

Primary trauma course |

450 physicians, 260 nurses, 119 clinical officers, and 111 medical students |

Thirty pre and post-MCQ exams, and 8 confidence matrix items |

Mean knowledge improved from 58% to 77% (p<0.05) confidence enhanced from 68% to 90%, with a mean of 22% (p<0.05) |

2 |

| Nogaro, 2015 |

Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Mozambique Zimbabwe |

Primary trauma care |

240 doctors and surgeons, 105 non-doctors |

Thirty pre and post-MCQ exams alongside 8 confidence matrix items |

Median knowledge improved from 70% pre-to 87% post-course (p<0.05). Following the PTC course, 91% of candidates demonstrated a substantial gain in knowledge. The median improvement exceeded 17% (p<0.05), and a 20% increment was noted in participants’ confidence in managing trauma scenarios. |

2 |

| Ologunde, 2017 |

Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe |

Primary trauma care |

253 (56.1%) physicians 98 (21.8%) nurses, 44 (9.8%) medical students and 40 (8.9%) clinical officers |

A survey following training; immediately and six months after the course completion |

Six months after training, 92.7% of respondents indicated improved trauma management, with 52.8% using a systematic or ABCDE approach. Departmental changes to trauma care were moderate (30%), with 23% of respondents indicating no change. Only 24.8% of respondents perceived improvement in trauma patient mortality and morbidity. |

4 |

| Tolppa, 2020 |

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

Primary trauma care |

Twenty-three nurses and 36 doctors |

20 pre and post-MCQ exams alongside 8 confidence matrix items, and repeated within two years |

Despite sustained gains in post-training exam scores over two years, confidence skills severely deteriorated (p=0.03). Additionally, the majority (95%) strongly agreed with the importance of trauma services; fifty-two attendees believed alternative procedures were needed to manage local patients, while thirty-six respondents mentioned a paucity of equipment. |

2 |

| Note: The table presents the description of primary trauma courses conducted across Sub-Saharan Africa, as selected from the electronic database. The columns of the table elaborate on the first author's name, the location of the course conducted, course attendees, course assessment modes, and outcomes, and Kirkpatrick evaluation levels. |

Table 2: Trauma course description in Sub-Saharan Africa selected from the electronic database.

Results

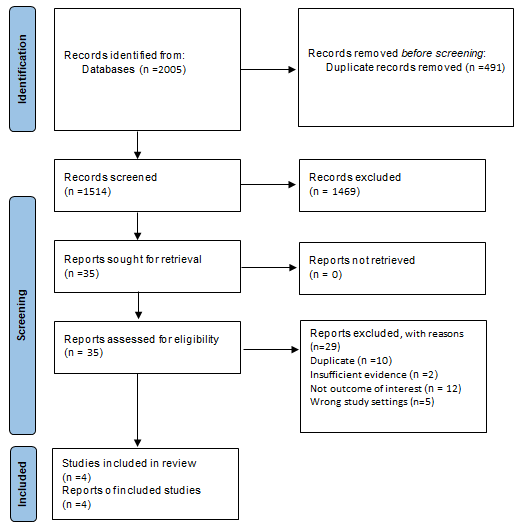

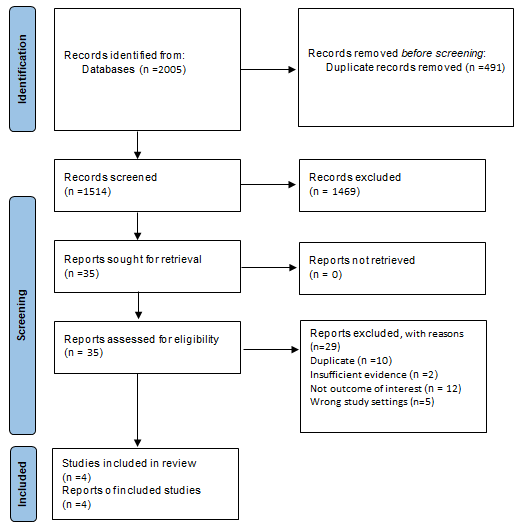

Figure 1 highlights the process of identifying and selecting the articles included in this review. Through MEDLINE (Ovid interface), Embase (Ovid interface), global health (Ovid interface), and African journal online databases, we identified 2005 citations. After completing all search strategies, 1514 records underwent title and abstract screening, of which 35 articles were kept undergoing full-text screening. After both stages of screening, 4 articles were included in this review. Of the included articles, all were original research and peerreviewed.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow chart for literature review.

Audience and Course Settings

A total of 2758 PTC course participants were recruited. The training is held entirely in SSA’s urban and rural settings. The bulk of studies reported on nurses and clinical officers (1624/2758, 58.9%), followed by physicians (979/2758, 35.5%) and medical students (155/2758, 5.6%). The complete course descriptions can be found in Table 2. Except for one study conducted at a single site, the other three were delivered in the ten member countries of The College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa (COSECSA). The COSECSA-Oxford-Orthopedic Link initiative, financed by the United Kingdom, developed and presented the PTC programs in collaboration with the University of Oxford. The program was delivered in a 2:1:2 cascade fashion, with an initial 2-day provider training, a 1-day instructor class, and a 2-day provider class offered by the newly minted instructors. Overseas instructors from developed nations taught the inaugural 2-day provider course, despite COSECSA coordinating the program.

Local Adaptability and Engagement

All studies involved local stakeholders by co-facilitating, delivering courses, and running training. Needs assessments were finalized beforehand and identified potential factors, including resource, workforce, infrastructure, trauma, and acute surgical disease burdens, existing training, gaps in training, and future recommendations, as well as financial concerns and the program's adaptability and mode of delivery.

Course Effectiveness

Participant-related outcomes (knowledge, skill, and con idence): Three articles reported the PTC course delivery's effects on increasing participants’ knowledge before and after training. The trainees completed Multiple-Choice Question (MCQ) tests. Following the PTC course completion, the two articles’ participants demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in trauma care knowledge (p<0.05), with a median ranging from 17% to 67.5%. For the third paper, trainees took the MCQ test before the course and 24 months after training completion and discovered sustainable gain in knowledge.

Two publications investigated how confidently participants felt handling trauma cases after the course delivery. In both studies, 1285 participants improved their confidence following the PTC course, with a mean improvement of 22 and 20%, respectively, which was statistically significant (p<0.05). These articles compared practitioners' knowledge and confidence advancement. Compared to physicians (17% and 18%), non-physicians (20% and 22%) appeared to boost their knowledge and confidence levels, respectively.

Ologunde et al., discovered that an immediate assessment showed that 13.1% of attendees improved specific skills in traumatic patient care. The authors further assessed longterm knowledge retention after completing the PTC course 321 participants across 86 hospitals in 10 countries in East, Central, and Southern Africa surveyed, 53% responded that adopting an ABCDE or systematic approach in the six-month follow-up. Of the participants, 92.7% reported having changed trauma patients' management scope by implementing the ABCDE approach, except 3.1% admitted not having gained changes. The authors further said that 77% expressed improvements in departmental injury care; 26% claimed increments in the workforce; 29% confirmed improved infrastructure; and 68% confirmed readiness to instruct other medical professionals in PTC. Furthermore, several participants witnessed enhancements in pre-hospital care, teamwork, communication, and skills.

In another study by Tolppa et al., there were improvements in knowledge assessment using MCQ scores (4.8) and a 9.6- boosting confidence score (p<0.01) immediately following the PTC. Despite increased knowledge retention 24 months after the course, trainees' confidence dropped (p<0.03). At the follow-up surveys, 36 of the 59 participants reported a lack of operative infrastructure, and 52 claimed extended procedures could be done to properly manage injured patients with local facilities. However, most agreed that trauma services were crucial, and the course attributed to improved trauma patient management.

Patient-related outcomes (mortality, morbidity, and complication): Except for a study by Ologunde et al., none evaluated patient outcomes following the PTC course. The authors narrated that the majority failed to show evidence besides a handful of responders providing accurate information on mortality and morbidity improvements six months after course delivery. Only 25% of participants admitted to traumatic patients' mortality and morbidity reduction within their department. However, neither of the publications compared outcomes to pre-course parameters or investigated long-term patient mortality and morbidity for longer than a year.

Cost Effectiveness

Only one study of the four published articles estimated the cost-effectiveness of PTC training. Peter et al. was the only study to report on the costs. Accordingly, the actual price for a primary five-day PTC course was anticipated to be $7706, while $5533 for a cascading one. However, in their study, a cascading system cost $184, while candidates taking a 2:1:2 primary PTC course cost $256.

Discussion

Advancing Practitioners’ Knowledge, Skill, and Performance

This is the first evaluation to summarize PTC training in SSA comprehensively. We found numerous initiatives to appraise PTC trauma training courses across SSA. Still, there needs to be more clarity about such a course's efficiency, appropriateness, and durability over the foreseeable future in SSA. According to the studies cited in this one, taking a PTC course enhances candidates' knowledge and confidence when handling critical trauma scenarios. These results were shown across a broad spectrum of applicants, including clinical personnel who were allied healthcare professionals, nurses, and physicians. Staff members who were non-physicians demonstrated the highest progress in confidence and knowledge. This affirms that the PTC course is significant, practical, and informative for medical practitioners, particularly in areas with a severe scarcity of clinicians. According to publications, researchers discovered strong evidence linking knowledge to improved patient outcomes and healthcare personnel performance.

Enhancing Facility Infrastructures

The PTC training produces better trauma care systems and significantly improved clinical settings. According to Ologunde et al., participants recognized deliberate and realistic advances in their systematic management of trauma patients. This was in line with Shi et al., narration of departmental and institutional benefits following the course delivery. As a result, trauma patients experienced shorter pre-hospital transfer times while avoiding extended waiting to receive prompted trauma care. Further, delivering local capacity-building for untrained staff by PTC-accredited personnel demonstrates their readiness to incorporate PTC concepts in training frontline personnel to effectively organize trauma teams to manage complex traumatic patients. Moreover, PTC strengthens the central concepts outlined in the WHO emergency care systems approach to benefit institutional healthcare.

A study by Tolppa et al., further demonstrated the necessity of the PTC course in enhancing overall trauma management approaches. According to the authors, most course participants strongly agreed with the training components that brought effectiveness to trauma services. However, over half of the surveyed trainees complained that the PTC training failed to equip them as anticipated for multifactorial reasons, including a shortage of procedure-related infrastructures. These are essential in exposing the facility to fill the abovementioned shortcomings.

Impact on Patient-Related Outcomes

Introducing trauma management courses addressed major trauma's burden on morbidity and mortality. Regarding reducing trauma-related mortality, we found a study revealing the impact of PTC courses on practitioners handling critical patients. Ologunde et al., demonstrated statistically significant beneficial effects in an institution where traumatized patients were included. Without considering additional confounding variables, it is challenging to determine the precise amount of mortality reduction driven by immediate PTC courses. Several restrictions remain, even if the research indicates improvements in patient outcomes alongside participants' knowledge and confidence.

Several studies evaluated participants' knowledge and confidence using standardized training questions to assess immediate knowledge retention post-training. Thus, it is challenging to determine whether these research findings significantly correlate with enhancing the effectiveness of trauma treatment and reducing mortality rates. Studies further support such narration; despite being the gold standard approach for dealing with severe trauma in higherincome countries, there remains conclusive evidence supporting the benefits of ATLS training on mortality reduction in SSA. Additional research is needed to determine if systematic approaches to trauma care using the PTC course's concepts bring gross positive patient outcomes.

Long-Term Knowledge Retention and Sustainability

As WHO's guidelines for trauma quality improvement programs emphasized, recertification is crucial to continuing medical education. Recertifying trainees following training completion was not mentioned in any articles reviewed. This ascertains doubts about the sustainability of the course and the moral obligation to give participants chances to update their current understanding and abilities, along with addressing areas requiring PTC courses' improvement. Substantial evidence has been found in publications associating knowledge with advancements in professional performance and patient outcomes. However, only one study evaluated knowledge retention within 24 months of posttraining. Accordingly, the authors discovered severe deterioration in trainees’ skills and confidence despite gaining knowledge. Importantly, studies of knowledge attrition within a year of training are comparable to those after ATLS accreditation. This emphasizes the importance of engaging in trauma care regularly or growing steadily through refresher sessions to keep skills and knowledge up to date.

Furthermore, as shortcomings, inadequate follow-up restricted the PTC program appraisal regarding training expenses. Most of the PTC training is covered by sponsorships, indicating that the global surgery programs still need to secure decent funding. Such a critical training program is only enhanced through a robust global funding network to advance trauma care for better outcome assessments, including longer follow-up sessions to ensure sustainability.

Conclusion

This research article is a landmark in its comprehensive analysis of PTC courses in SSA. The research has demonstrated the impact and effectiveness of PTC training implementation in SSA although there is limited evidence for standardizing trauma care in such resource-limited settings. Additional formal PTC training for trauma team members in SSA results in divisional, organizational, and individual benefits in medical practice. These findings lend credence to the idea that official PTC training should expand for all professionals serving as first responders in SSA. Based on the findings of the published article, we can assert that PTC courses have the potential to serve as a cost-effective alternative to ATLS training, particularly in resource-limited settings such as SSA. However, it is important to note that additional research and evaluation may be required to further substantiate this claim, particularly regarding its impact on advancing healthcare knowledge, and skill development, increasing healthcare providers' confidence, and improving patient outcomes over an extended period.

Limitations

This study's limitations may be considered when interpreting the findings. This study’s literature on PTC programs was accessed only from online sources and English publications. Still, it remains conceivable that it overlooked web-based or non-English articles. Another limitation of this study is the limited sample size as we concentrated solely on trained medical practitioners providing definitive trauma care in SSA to maintain the research's focus and conciseness. These collectively restricted the breadth of our findings, resulting in a simplistic illustration of PTC training in SSA. However, despite this, the study provided insight into published articles regarding PTC courses in SSA.

Authors' Contributions

CO and TR conceived the article ideas. CO wrote the manuscript draft. CO, TR, JG, and DD designed the study and analysis, revised the manuscript, and provided critical reviews. All authors have given their agreement for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Murray CJ, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, Lim SS, Wolock TM, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 384(9947):1005-1070.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (2022) WHO consultation to adapt influenza sentinel surveillance systems to include COVID-19 virological surveillance: Virtual meeting, 6-8 October 2020. World Health Organization.

[Google Scholar]

- Mock C, Joshipura M, Arreola-Risa C, Quansah R (2012) An estimate of the number of lives that could be saved through improvements in trauma care globally. World J Surg. 36:959-963.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hanche-Olsen TP, Alemu L, Viste A, Wisborg T, Hansen KS (2015) Evaluation of training program for surgical trauma teams in Botswana. World J Surg. 39:658-668.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bundu I, Lowsby R, Vandy HP, Kamara SP, Jalloh AM, et al. (2019) The burden of trauma presenting to the government referral hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone: An observational study. Afr J Emerg Med. 9:S9-S13.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reynolds TA, Stewart B, Drewett I, Salerno S, Sawe HR, et al. (2017) The impact of trauma care systems in low-and middle-income countries. Annu Rev Public Health. 38(1):507-532.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mock CN, Quansah R, Addae-Mensah L, Donkor P (2005) The development of continuing education for trauma care in an African nation. Injury. 36(6):725-732.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carmont M (2005) The advanced trauma life support course: A history of its development and review of related literature. Postgrad Med J. 81(952):87.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohammad A, Branicki F, Abu-Zidan FM (2014) Educational and clinical impact of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses: A systematic review. World J Surg. 38:322-329.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jayaraman S, Sethi D, Chinnock P, Wong R (2014) Advanced trauma life support training for hospital staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petroze RT, Byiringiro JC, Ntakiyiruta G, Briggs SM, Deckelbaum DL, et al. (2015) Can focused trauma education initiatives reduce mortality or improve resource utilization in a low-resource setting?. World J Surg. 39:926-933.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chokotho L, Jacobsen KH, Burgess D, Labib M, Le G, et al. (2016) A review of existing trauma and musculoskeletal impairment (TMSI) care capacity in East, Central, and Southern Africa. Injury. 47(9):1990-1995.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kornfeld JE, Katz MG, Cardinal JR, Bat-Erdene B, Jargalsaikhan G, et al. (2019) Cost analysis of the Mongolian ATLS© Program: A framework for low-and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 43:353-359.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammerstedt H, Maling S, Kasyaba R, Dreifuss B, Chamberlain S, et al. (2014) Addressing World Health Assembly Resolution 60.22: a pilot project to create access to acute care services in Uganda. Ann Emerg Med. 64(5):461-468.

[Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DP, McDougall R (2007) Primary trauma care. Anaesthesia. 62:61-64.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- PTC Foundation (2019) Primary Trauma Care.

- Jawaid M, Memon AA, Masood Z, Alam SN (2013) Effectiveness of the primary trauma care course: Is the outcome satisfactory?. Pak J Med Sci. 29(5):1265.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ley Greaves RA, Wilkinson LF, Wilkinson DA (2017) Primary trauma care: A 20-year review. Trop Doct. 47(4):291-294.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peter NA, Pandit H, Le G, Nduhiu M, Moro E, et al. (2016) Delivering a sustainable trauma management training programme tailored for low-resource settings in East, Central and Southern African countries using a cascading course model. Injury. 47(5):1128-1134.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tolppa T, Vangu AM, Balu HC, Matondo P, Tissingh E (2020) Impact of the primary trauma care course in the Kongo Central province of the Democratic Republic of Congo over two years. Injury. 51(2):235-242.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Osebo C, Grushka J, Deckelbaum D, Razek T (2025) Empowering Healthcare through Education: Is the Primary Trauma Care Course Impactful in Sub-Saharan Africa?: A Literature Review. J Intensive Crit Care. 11:56.

Copyright: © 2025 Osebo C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.