Research Article - (2025) Volume 10, Issue 1

Associations of Maternal Age and Body Mass Index (BMI) with Birth Weight: A Generalized Additive Model

Tesfaye Getachew Charkos* and

Hunde Lemi

Department of Public Health, Adama Hospital Medical College, Adama, Oromia, Ethiopia

*Correspondence:

Tesfaye Getachew Charkos, Department of Public Health, Adama Hospital Medical College, Adama, Oromia,

Ethiopia,

Email:

Received: 03-Sep-2023, Manuscript No. IPPHR-23-17653;

Editor assigned: 05-Sep-2023, Pre QC No. IPPHR-23-17653 (PQ);

Reviewed: 19-Sep-2023, QC No. IPPHR-23-17653;

Revised: 21-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. IPPHR-23-17653 (R);

Published:

28-Jan-2025, DOI: 10.36648/2574-2817.10.1.36

Abstract

Background: Epidemiological studies examining the impacts of maternal age and body mass index on the birth weight of a newborn is still sparse. We aimed to investigate the relationship between maternal age and body mass index with birth.

Methods: This cross-sectional study identified females aged 15 to 49 years with complete and valid data on the maternal age, maternal body mass index, and birth weight of newborns from the Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016. Linear regression and Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) were used in this study.

Results: A total of 2110 females were included, with the average of BW, LBW, and macrosomia were 3280 g, 1920 g, and 4880 g respectively. After adjusting all covariates, we found that a one-year increment of maternal age was associated with 6.375 g increases in the birth weight of the newborn. Similarly, maternal BMI was positively and negatively associated with birth weight (β=0.323, P<0.001) and macrosomia (β=-0.041, P<0.05) respectively. There also approximately a linear relationship was found between maternal age and BMI with birth weight in the generalized additive model.

Conclusion: These findings confirm that a maternal age and body mass index have positive and linear relationship with birth weight of newborn. Similarly, the body mass index of the mothers has a direct impact on the macrosomia.

Keywords

Maternal age; Body mass index; Birth weight; Macrosomia; Generalized additive model

Introduction

Abnormal Birth Weight (BW) is the most important factor for infant mortality, birth defects, risk of various diseases in adulthood [1,2]. This abnormal BW should include Low Birth Weight (LBW) less than 2500 g and macrosomia greater than 4000 g, which leads to an adverse effect on the intrauterine growth and development of newborns, is a marker of age related disease risk [3,4]. Studies suggested that low birth weight infants have a 20 times greater likelihood of dying compared to infants of normal birth weight [5,6]. Birth weight may serve as a convenient surrogate for other factors causally associated with mortality, hypertension, diabetes, and other metabolic diseases [7]. The incidence of abnormal BW is generally high in the world, it was estimated that 5-7% of LBW occurred in developed countries, and approximately 19% in developing countries [8]. A recent study reported that the average incidence of LBW in Ethiopia was reported as 17.1%, which is the highest prevalence [9].

Recently, the relationship between maternal ages and birth weight of the newborn was getting an attention. Some studies suggested that advancing in maternal age (≥ 35 years) was associated with increasing stillbirths, preterm births, intrauterine growth restriction, as well as young maternal age, and chromosomal abnormalities [10-13]. Gibbs et al., findings suggested that teenage mothers have a higher risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, low Apgar score, and postnatal mortality [14]. Maternal body weight may have an independent adverse effect on birth weight and newborn growth. In low-income countries such as Ethiopia, no studies were conducted to assess the effects of teenage, extreme childbearing age, and maternal body mass index on the birth weight. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the relationship between maternal age and body mass index with birth weight using a generalized additive model.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) is a cross sectional and population-based survey conducted to obtain a comprehensive overview of population, maternal, and child health indicators [15]. It was implemented by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) at the request of the Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH). The state was divided into nine regions and two administrative cities. Briefly, each region was stratified into urban and rural areas, yielding a total of 21 sampling strata. The sampling frame was a list of all Enumerator Areas (EAs) stratum. Within each stratum, a two-stage sample was selected. In the first stage, a total of 645 EAs were selected with probability proportional to EA size (based on the 2007 People and Housing Census) and with independent selection in each sampling stratum. In the second stage of selection, a fixed number of 28 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability systematic selection from the newly created household listing.

Study Measures

In all of the selected households, each woman interviewed in the survey was asked to provide a detailed her age at recent birth, history of all her live births in chronological order, sex of the child, height and weight measurements were collected from women age 15-49, anemia, place of delivery, place of residence, higher education level, wealth index and birth weight of the newborn child. Anemia testing was performed on consenting women. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by squaring of body height (m2). In this study, we used to determine the relationship between maternal age and body mass index with Birth Weight (BW), low birth weight, and macrosomia. Where Low Birth Weight (LBW) was defined as BW less than 2500 g [16]. Macrosomia was defined as above the standard birth weight, which is a birth weight greater than or equal to 4000 g [17].

Statistical Analysis

In the descriptive analysis, continuous variables with normal distribution were shown as means (SDs), and categorical variables were shown as absolute frequency and percentages. In this study, we used multivariate linear regression models to test the relationship between maternal age and BMI with birth weight, low birth weight, and macrosomia. In the analysis, all multivariate linear regression models were adjusted for a place of residence, maternal anemia status, child of sex, place of delivery, highest education level, wealth index of the family, and antenatal care follow up. Although, Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) were used to testing the potential non-linear relationships of maternal age and BMI with birth weight, low birth weight, and macrosomia. Similarly, the GAMs were applied by adjusting the same covariates as multivariate linear regression models. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version: 25.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL), R software (version: 3.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (Version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

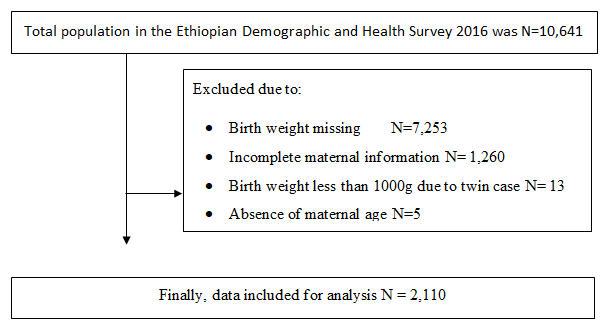

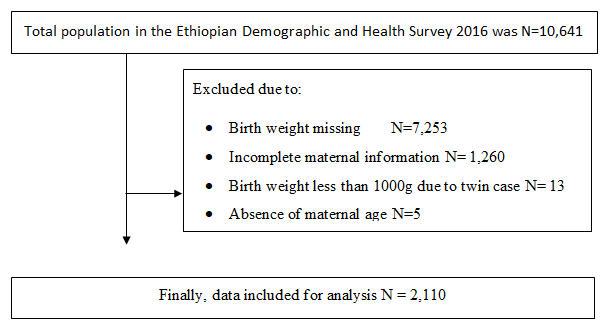

After excluding individuals who did not meet the study criteria, we included 2110 newborns from the Ethiopian demographic and health survey 2016. The excluded subjects were due to birth weight missing (N=7253), incomplete maternal information (N=1260), birth weight less than 1000 g as a reason of twin birth (N=13), absence of maternal age (N=5) (Figure 1). The average age of the participants was 28.49 years, with the average BMI, BW, LBW, and macrosomia was 26.70 kg/m2, 3277.04 g, 1919.59 g, and 4880 g respectively (Table 1). Out of a total, 60.47% of the subjects were urban residence and only 39.53% were rural residence. The majority of the mothers were free of anemia disease (69.05%) and poor category of wealth index (75.69), only 0.38%, 5.12%, and 17.73% are severe, moderate, and mild anemia status respectively. From our sample data, 95.88%was delivered in the health center.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for the selection of 1 newborns in the study.

| Variables |

Value |

| Age of mothers (years) |

28.49 (6.08) |

| Place of residence |

| Urban |

1276 (60.47) |

| Rural |

834 (39.53) |

| Mothers anemia status |

| Severe |

8 (0.38) |

| Moderate |

108 (5.12) |

| Mild |

374 (17.73) |

| Not anemic |

1457 (69.05) |

| Child of sex |

| Male |

1078 (51.09) |

| Female |

1032 (48.91) |

| Place of delivery |

| Home |

76 (3.60) |

| Health center |

2023 (95.88) |

| Education level |

| No education |

564 (26.73) |

| Primary school |

787 (37.30) |

| Secondary school |

429 (20.33) |

| Higher |

330 (25.64) |

| Wealth index of the family |

| Poor |

1597 (75.69) |

| Mild |

389 (18.44) |

| Rich |

124 (5.88) |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) |

26.70 (18.03) |

| Birth weight (in gram) |

3277.04 (829.92) |

| Low birth weight (in gram) |

1919.59 (827.82) |

| Macrosomia (in gram ) |

4880.14 (820.20) |

Table 1: Characteristics of mothers and newborns included from Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016 (EDHS).

Table 2 shows the results of multivariate linear regression models for the predictors of birth weight, low birth weight, and macrosomia. After adjusting for a place of residence, mothers anemia status, child of sex, place of delivery, highest education level, wealth index of the family, and antenatal care follow up, we found that maternal age (β=6.375; P=0.032) was associated with a birth weight of the newborn. In which, a one-year increment of maternal age was associated with 6.375 g increases in the birth weight of the newborn. Also, BMI was significantly associated with birth weight (β=0.323) and macrosomia (β=-0.041) (Table 2) all P<0.05). In this study, the impacts of maternal age and BMI on low birth weight were not observed.

| Independent variable |

Dependent variable |

β (p)* |

| Maternal age |

Birth weight |

6.375 (0.032) |

| Low birth weight |

5.135 (0.210) |

| Macrosomia |

-0.157 (0.977) |

| BMI |

Birth weight |

0.323 (<.001) |

| Low birth weight |

-0.002 (0.901) |

| |

Macrosomia |

-0.041 (0.016) |

| Note: *Values were adjusted for a place of residence, a number of visits for antenatal care, education level of the mother, wealth index, smoking status, occupations of the mother, and place of birth. |

Table 2: Associations of maternal age and Body Mass Index (BMI) with birth weight, low birth weight, and macrosomia in the multivariable linear regression models.

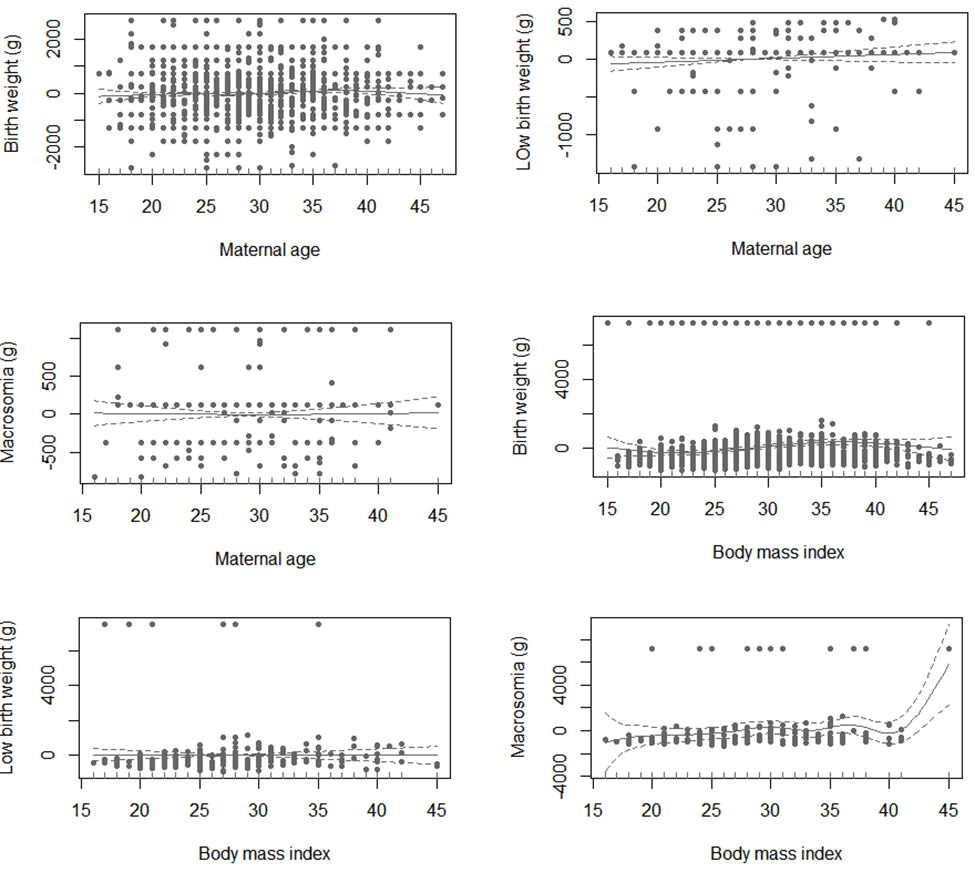

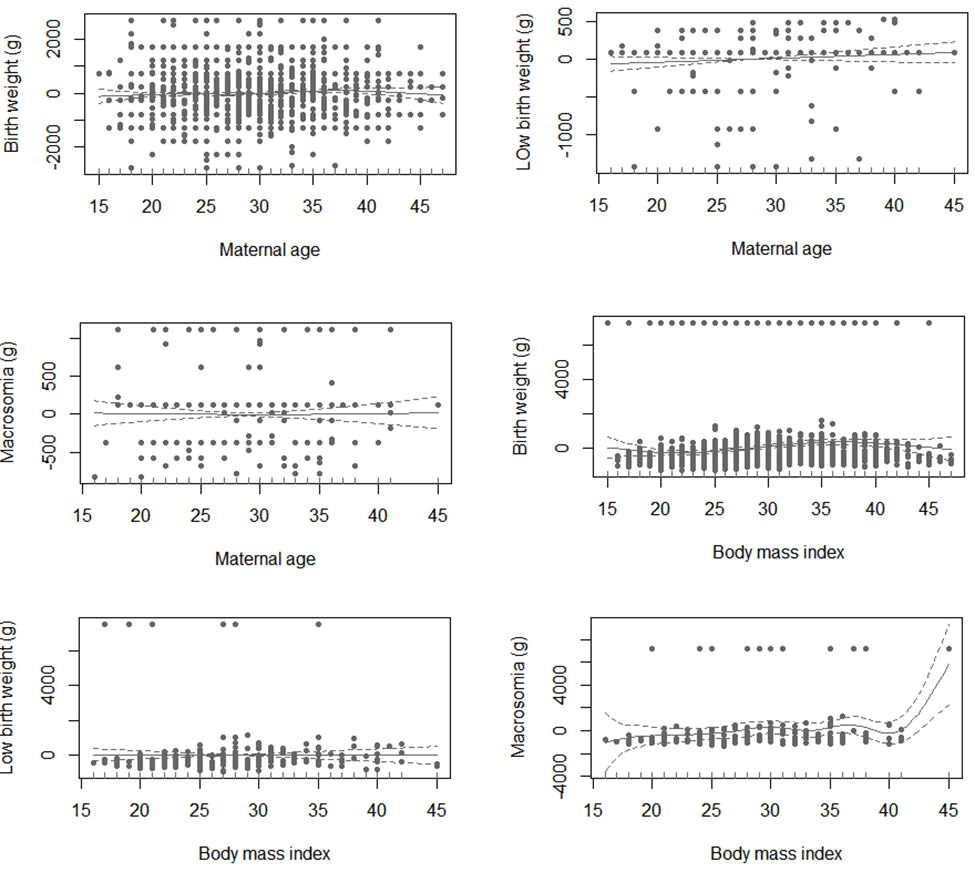

In the generalized additive model, both maternal age and body mass index were positively and approximately linear relationships with the birth weight of newborns (Figure 2). The relationship between body mass index and birth weight newborn were seemed more linear compared to maternal age.

Figure 2: Plot from a generalized additive model on the relationship between maternal age and body mass index with birth weight, low birth weight, and macrosomia. Association was adjusted for a place of residence, mother's anemia status, child of sex, place of delivery, education level of the mother, wealth index of the family, and antenatal care follow up

Discussion

In this population-based cross-sectional study, we observed that advancing in childbearing age was associated with an increased birth weight of the newborn. Similarly, we found that Body Mass Index (BMI) was linearly associated with birth weight and macrosomia. These findings extended our understanding of the impact of maternal age and body mass index on the birth weight of the newborn.

A numerous studies shown that a maternal childbearing age was associated with newborn birth weight. Studies amongst Americans of different race and ethnic groups, have shown that middle age mothers (>30 years) were most at risk of delivering LBW babies [18,19]. Similarly, a teenager (15-19 years) also had a significantly increased risk of delivering LBW babies as compared the normal childbearing age (25-29 years). Another studies suggested that advanced maternal age was an independent factor associated with LBW and preterm birth outcomes [20]. The LBW risk estimates associated with maternal age 35 years were 5.3% (95% CI, 4.7-6.0) among African Americans, 4.3% (95% CI 1.7-6.9) among Puerto Ricans, and 3.7% (95% CI 2.8-4.5) in Mexican Americans, compared with 2.6% (95% CI 2.4-2.7) in non-hispanic whites.

Consistently, several studies have shown a preterm as a major cause for low birth weight. Elena et al. conducted a cross sectional study of more than 42,000 newborns and found that the height and body mass index of the mothers were significantly associated with the birth weight of the newborn. Although a report from previous demonstrated that a maternal age was an independent risk factor for preterm delivery [20]. A prospective cohort study on the healthy women with a single pregnancy, reported increasing adjusted odds ratios for preterm delivery with increasing maternal age, after adjusting for demographic characteristics, smoking, history of infertility, and other medical conditions. In addition, another Swedish research studying 2,009,068 birth found that advanced maternal age is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, especially very preterm birth, irrespective of parity, (adjusted ORs 1.18 to 1.28 at 30-34 years, from 1.59 to 1.70 at 35-39 years, and from 1.97 to 2.40 at ≥ 40 years). This all together indicates that the preterm delivery is one of independent factors for birth weight.

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study that investigated the linear and potentially non-linear relationships between maternal age and body mass index with birth weight, low birth weight, and macrosomia using linear regression and generalized additive model respectively. In this study, we found important findings; the relationship between maternal age and body mass index with birth weight and macrosomia were appeared to be linear.

Regardless of the biological mechanisms underlying the relationship between BMI and birth weight is still unclear. However, some studies suggested that maternal BMI may have direct physiological influences on fetal growth determining nutrient supply and hormone profiles. Obese women have an adverse outcome on the pregnancy, and the fetus of an obese mother has an increased risk of stillbirth and birth defects. In this, a fetal overgrowth is common in pregnancies of women with increased Body Mass Index (BMI) and results in the birth of a large-for-gestational-age infant (typically defined as a birth weight greater than the 90th percentile). Even though birth weight is also determined by a combination of intrauterine, genetic, and environmental factors. In our study, we also found that a body mass index was related with birth weight of the newborn, this is in line with the findings of previous studies.

Some limitations need to be mentioned: First, due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot explore the causal for low birth weight rather we assessed the association between maternal age and BMI with birth weight. Second, even though the Ethiopian demographic and health survey data are nationally representative, the household with a history of birth are small in size; this may partly affect our finds.

Conclusion

This study found a linear relationship between maternal age and the birth weight of the newborn. Similarly, the body mass index was observed as a positive linear relationship with birth weight and macrosomia. A 1 kg/m2 increase in body mass index was associated with a 0.323 g and 0,509 g increase in birth weight and macrosomia respectively. Further studies are warranted to confirm our findings.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program for availing the data

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization of study, Analysis of the data, Writing the first draft, Writing review and editing was done by solely TGC.

Funding

Not available.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The data analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Kiserud T, Benachi A, Hecher K, Perez RG, Carvalho J, et al. (2018) The World Health Organization fetal growth charts: Concept, findings, interpretation, and application. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 218(2):S619-S629.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim MA, Yee NH, Choi JS, Choi JY, Seo K (2012) Prevalence of birth defects in Korean livebirths, 2005-2006. J Korean Med Sci. 27(10):1233-1240.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reif S, Wichert S, Wuppermann A (2018) Is it good to be too light? Birth weight thresholds in hospital reimbursement systems. J Health Econ. 59:1-25.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He JR, Li WD, Lu MS, Guo Y, Chan FF, et al. (2017) Birth weight changes in a major city under rapid socioeconomic transition in China. Sci Rep. 7(1):1031.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCormick MC (1985) The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med. 312(2):82-90.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilcox AJ (2001) On the importance and the unimportance of birthweight. Int J Epidemiol. 30(6):1233-41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF (2007) Low birth weight in the United States. The Am J Clin Nutr. 85(2):584S-590S.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vaiserman AM (2018) Birth weight predicts aging trajectory: A hypothesis. Mech Ageing Dev. 173:61-70.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeleke BM, Zelalem M, Mohammed N (2012) Incidence and correlates of low birth weight at a referral hospital in Northwest Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 12(1).

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carolan M, Frankowska D (2011) Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome: A review of the evidence. Midwifery. 27(6):793-801.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ngowa JD, Ngassam AN, Dohbit JS, Nzedjom C, Kasia JM (2013) Pregnancy outcome at advanced maternal age in a group of African women in two teaching Hospitals in Yaounde, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 14.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kenny LC, Lavender T, McNamee R, O’Neill SM, Mills T, et al. (2013) Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: Evidence from a large contemporary cohort. PloS One. 8(2):e56583.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newburn-Cook CV, Onyskiw JE (2005) Is older maternal age a risk factor for preterm birth and fetal growth restriction? A systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 26(9):852-875.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibbs CM, Wendt A, Peters S, Hogue CJ (2012) The impact of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 26:259-284.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hughes MM, Black RE, Katz J (2017) 2500-g low birth weight cutoff: History and implications for future research and policy. Matern Child Health J. 21:283-289.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye J, Torloni MR, Ota E, Jayaratne K, Pileggi-Castro C, et al. (2015) Searching for the definition of macrosomia through an outcome-based approach in low-and middle-income countries: A secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey in Africa, Asia and Latin America. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 15:1-0.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reichman NE, Pagnini DL (1997) Maternal age and birth outcomes: Data from New Jersey. Fam Plann Perspect. 268-295.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aldous MB, Edmonson MB (1993) Maternal age at first childbirth and risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery in Washington State. JAMA. 270(21):2574-2577.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delpisheh A, Brabin L, Attia E, Brabin BJ (2008) Pregnancy late in life: A hospital-based study of birth outcomes. J Womens Health. 17(6):965-970.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khoshnood B, Wall S, Lee KS (2005) Risk of low birth weight associated with advanced maternal age among four ethnic groups in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 9:3-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Charkos TG, Lemi H (2025) Associations of Maternal Age and Body Mass Index (BMI) with Birth Weight: A Generalized

Additive Model. Pediatr Health Res. 10:36.

Copyright: © 2025 Charkos TG, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.