Case Report - (2025) Volume 11, Issue 1

A Rare Case of Blunt Left Diaphragmatic and Pericardial Rupture in a Child: A Case Report

Melaku Tessema Kassie*,

Motuma Gonfa,

Ruth Betremariam Abebe and

Befikadu Molalign

Department of Surgery, University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health sciences, Gondar, Ethiopia

*Correspondence:

Melaku Tessema Kassie, Department of Surgery, University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health sciences, Gondar,

Ethiopia,

Tel: 251932289585,

Email:

Received: 25-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. IPJICC-24-18953 ;

Editor assigned: 29-Jan-2024, Pre QC No. IPJICC-24-18953 (PQ);

Reviewed: 12-Feb-2024, QC No. IPJICC-24-18953 ;

Revised: 24-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. IPJICC-24-18953 (R);

Published:

31-Jan-2024, DOI: 10.36648/2471-8505.11.1.57

Abstract

Introduction: Blunt Diaphragmatic Rupture (BTDR) is a rare condition that can occur in children following high-energy blunt thoracoabdominal trauma. In less than 1% of the cases, pericardial rupture can coexist with a BTDR. A coexistence of BTDR and pericardial rupture can result in displacement of the heart and is associated with high mortality. Clinical presentation is non-specific and requires a high index of suspicion for early management.

Case presentation: A 4-year-old child presented to the emergency unit following high-energy trauma with severe respiratory distress. Initially, a left side chest tube was inserted but showed no clinical improvement. A chest X-ray showed a collapse of the left lung with herniation of bowel loops into the left hemithorax. An exploratory laparotomy was done and revealed a 10 × 4 cm defect in the left hemidiaphragm with a medial extension involving the pericardium. The fundus of the stomach and left lobe of the liver were displaced into the pericardial space. Concomitantly, the transverse colon and small bowl were displaced into the left pleural space. After the reduction of the herniated abdominal viscera back into the peritoneal cavity, the pericardial sac was repaired by an interrupted resorb able suture while the diaphragmatic defect was repaired by a horizontal mattress. No other injuries were identified and the abdomen was closed in layers.

Conclusion: BTDR with pericardial rupture is an elusive condition with a high mortality rate that needs a high index of clinical suspicion. Early surgical repair of the defect with reduction of herniated organs can reduce morbidity and mortality.

Keywords

Blunt trauma; Diaphragmatic rupture; Pericardial tear; Pediatric trauma; Tension pneumothorax; Tube thoracostomy

Introduction

Diaphragmatic rupture following blunt abdominal trauma is a rare case scenario with an incidence ranging from 1-7% [1]. Incidence is particularly low in children with less than 1% of pediatric trauma resulting in diaphragmatic rupture [2,3]. Since most Blunt Traumatic Diaphragmatic Rupture (BTDR) result from high-energy traumas such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from height, patients often present with severe injuries to the other visceral organs [2,4-7].

Meanwhile, the coexistence of a pericardial rupture is very rare with an incidence of 0.2-3.3% [4]. Pericardial ruptures are associated with a high mortality rate [1,8,9]. Communication between the abdominal cavity and pericardial space through the tear can allow the herniation of abdominal organs into the chest cavity and pericardial space resulting in cardiac tamponade, respiratory compromise or gastrointestinal obstruction [1,8]. The management of choice is early reduction of hernia contents and repair of the defect [1,4,10]. We report a rare case BTDR with herniation of abdominal viscera into the chest cavity, and isolated pericardial rupture with subluxation of the heart.

Case Presentation

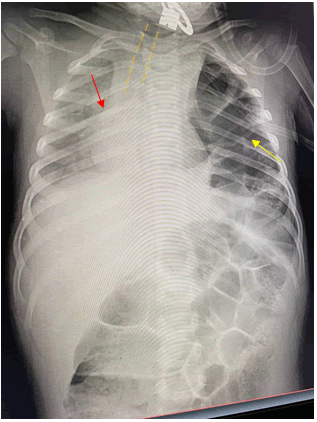

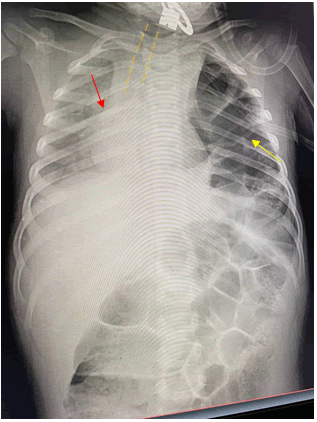

A 4-year-old male child presented to the emergency unit after he was hit by a high-velocity vehicle. At the emergency, he showed signs and symptoms of respiratory distress with RR-66 breaths/min, SpO2 of 66% at room air and 72% on a 10 L facemask. His blood pressure was 88/40 mmHg and pulse PR-144 beats/min regular. The child showed no signs of head injury or grossly visible fracture. Physical examination disclosed absent air entry and hyper resonance on the left side of the chest with abrasion over his left chest wall and flank. The initial impression was tension pneumothorax and a tube thoracostomy was inserted into the affected side. However, there was no gush of air or blood following neither tube thoracostomy nor clinical improvement. Subsequently, a chest X-ray revealed left lung compression, herniation of bowel loops into hemithorax, and mediastinal shift to the right side (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The yellow arrow indicates bowel loops with haustral marking and gas in the left hemi-thorax. The red arrow indicates a significant shift of the mediastinum to the right side. The image also shows significant tracheal deviation outlined by the yellow dashed line.

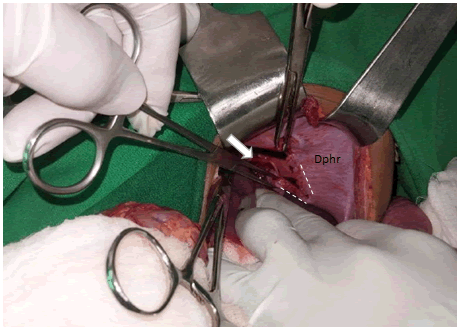

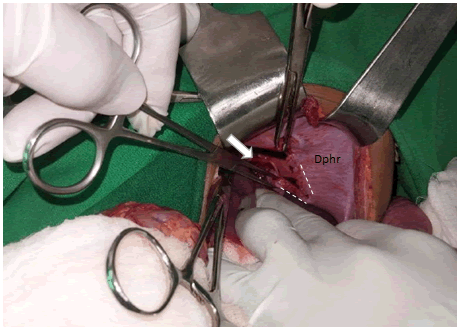

The patient was transferred to the operating room for emergency exploration. A left transverse abdominal incision was performed. About 200 ml of blood in the peritoneal cavity with no gross contamination was identified. There was also a 10 × 4 cm left hemi diaphragmatic defect with medial extension resulting in 4 × 2 cm pericardial sac defect (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The white arrow indicates the pericardial sac tear. The white dashed line outlines the diaphragmatic defect. "DPHR" labels the left hemi-diaphragm.

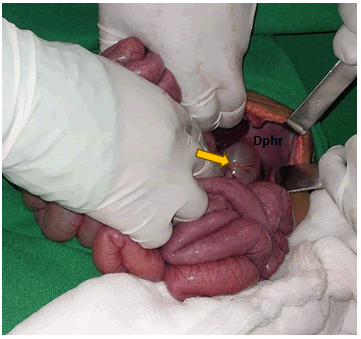

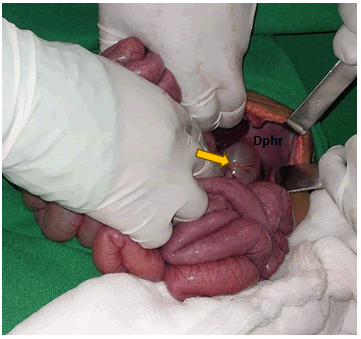

The transverse colon and proximal part of the small bowel herniated into the pleural cavity through the left hemi diaphragmatic defect with contusion of the transverse colon at the level of the defect (Figure 3). However, there was no bowel perforation.

Figure 3: The yellow arrow indicates the transverse colon, DPHR indicates the diaphragm.

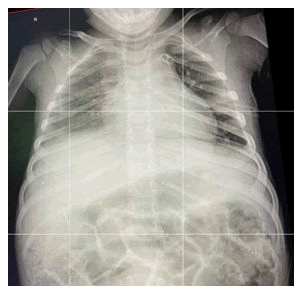

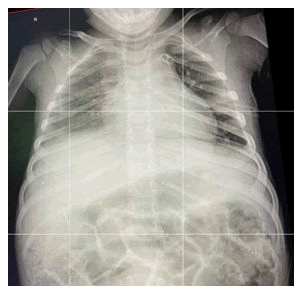

The edge of the left lobe of the liver and fundus of the stomach were uprooted into the pericardial space through the defect in the pericardium but no myocardial contusion was seen. The herniated abdominal viscera were reduced into the peritoneal cavity. Recruitment of the collapsed left lung was done until a complete expansion. No signs of air leak were evidenced post-expansion. The pericardial defect was primarily closed with interrupted resorb able sutures. The diaphragmatic defect was primarily closed with an interrupted horizontal mattress. The integrity of the repair and diaphragmatic motion was then checked via large tidal volume administration. No other visceral injuries were identified, and the abdominal wall was closed in layers. A chest tube was kept in place for 48 hours and removed after evaluation of a control chest X-ray (Figure 4).

Figure 4: AP chest X-ray taken 48 hours post operation prior to removal of chest tube.

Results and Discussion

Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture is the loss of integrity of the diaphragm due to a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure from trauma [10-12]. The most common site of rupture is at the junction of muscle and tendon [3]. Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture accounts for less than 0.5% of all trauma cases and 1.9% of all blunt traumas [11]. The incidence of Blunt Traumatic Diaphragmatic Rupture (BTDR) is lower in the pediatric age group standing at 0.18% of all pediatric traumas [2]. Most BTDRs occur in the left posterolateral section of the diaphragm owing to the cushion effect of the liver on the right side [5,8]. A systematic review by Theodorou CM showed a mortality rate of 2.8% among pediatric patients directly as a result of diaphragmatic rupture and associated herniation [2]. The overall mortality rate was reported to be 33% among pediatric patients in studies by the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) [2]. Patients with BTDR often present with injuries to the abdominal and chest organs [5]. One study found that liver and spleen injuries were discovered in 40-60% of pediatric patients with BTDR [2].

Although injury to different organs is commonly associated with BTDR, a pericardial tear is very rare and is associated with a high mortality rate reaching up to 64% [4,11]. Isolated pericardial tear in a patient with BTDR is even rarer [12]. However, our patient presented with an isolated pericardial rupture with BTDR. Following blunt trauma most pericardial ruptures occur over the left pleuro-pericardium [12]. Pericardial rupture is an elusive diagnosis with most cases identified intra-operatively [5,6]. Similarly, the defect in the pericardial sac of our patient was identified intra-operatively. Most patients with pericardial rupture are asymptomatic and only show signs and symptoms when there is an associated herniation of the heart or bleeding occurs [5]. Large defects in the pericardium can result in dislocation or torsion of the heart [12]. In our patient, there was subluxation of the cardiac apex to the right side and the defect was filled with herniated abdominal viscera preventing displacement of the heart out of the pericardial space through the defect.

The most common clinical symptoms of BTDR are signs and symptoms of respiratory distress followed by abdominal pain [2]. Signs and symptoms of respiratory compromise can lead to misdiagnosis of pneumothorax resulting in the insertion of a chest tube and iatrogenic injury to the herniated organ [12]. In our patient, a similar misdiagnosis was made, and a chest tube was wrongfully inserted. Fortunately, there was no iatrogenic injury to the herniated bowel segments. Plain films of the chest and/or abdomen are the most common imaging performed in acute cases with sensitivity ranging from 27-73% [5]. Findings on plain films associated with pericardial involvement include changes in the cardiac silhouette or axis, signs of pneumo-pericardium, and pericardial effusion [12]. Computed Tomography (CT) scans are more specific and sensitive compared to other imaging modalities to identify chest and abdominal injuries [5].

BTDR should be urgently repaired upon diagnosis especially, in left-sided diaphragmatic ruptures. Operative repair via abdominal approach is the most common management for primary repair of the diaphragm although the thoracic approach is recommended in cases of delayed diagnosis due to intra-abdominal adhesions from chronicity [2,10,11].

Conclusion

Diaphragmatic tear following blunt trauma is rare and is often associated with poly-trauma. An Isolated pericardial involvement is uncommon and difficult to detect preoperation. As such a high level of suspicion is required when evaluating patients with blunt trauma and respiratory distress. Emergent surgery with reduction of herniated viscera and primary closure of diaphragmatic and pericardial defects can result in better patient outcomes.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The case report has been submitted to the school of medicine at university of Gondar for ethical board review and approved as ethically sound report.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent was taken from the parents for publication of case report and any accompanying image. A copy of written consent is available for review for the editor in chief of this journal.

Availability of Data and Materials

The authors of this manuscript are willing to provide any additional information regarding the case report.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors Contribution

All authors contributed to the conception, writing and editing of the case report. All authors are agreed to be accountable for all aspects.

Funding

All authors declare that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted report.

References

- Feliciano VD, Mattox KL, Moore EE (2020) Trauma. 9th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education; United States.

- Theodorou CM, Jackson JE, Beres AL, Leshikar DE (2021) Blunt traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in children: A systematic review. J Surg Res. 268:253-262.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burhamah W, Matcovici M, Hardy A, Awadalla S (2020) Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture in children. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 61:101619.

[Google Scholar]

- Chellasamy RT, Rajarajan N, Samy NM, Munusamy H (2023) A rare case of traumatic pericardio-diaphragmatic injury following a road traffic accident. 15(5).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozalp T, Kupeli M, Sunmezoglu Y, Cakmak A, Akgul S, et al. (2017) Blunt diaphragmatic injuries: Pericardial ruptures. Indian J Surg. 79:212-218.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao R, Jia D, Zhao H, WeiWei Z, Yangming WF (2018) A diaphragmatic hernia and pericardial rupture caused by blunt injury of the chest: A case review. J Trauma Nurs. 25(5):323-326.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis PW (1968) Traumatic herniation into the pericardial sac. Postgrad Med J. 44(517):875.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okamoto S, Maeyama H (2023) Traumatic intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia. Acute Med Surg. 10(1).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abou Hussein B, Khammas A, Kaiyasah H, Swaleh A, Al Rifai N, et al. (2016) Pericardio-diaphragmatic rupture following blunt abdominal trauma: Case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 19:168-170.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oz N, Kargı AB, Zeybek A (2015) Co-existence of a rare dyspnea with pericardial diaphragmatic rupture and pericardial rupture: A case report. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 12(2):173-175.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Bakouri A, El Karouachi A, Bouali M, El Hattabi K, Bensardi FZ, et al. (2021) Post-traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with pericardial denudation: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 83:105970.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mude NN, Prakash S, Shaikh O, Vijayakumar C, Kumbhar U (2022) Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with pericardial tear and transdiaphragmatic herniation of the stomach. Cureus. 14(9).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Kassie MT, Gonfa M, Abebe RB, Molalign B (2025) A Rare Case of Blunt Le t Diaphragmatic and Pericardial Rupture in a

Child: A Case Report. J Intensive Crit Care. 11:57.

Copyright: © 2025 Kassie MT, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original author and source are credited.